Description

aWoodsonas novel skillfully weaves in the music and events surrounding the rising opposition to the Vietnam War, giving this timeless story depth. She raises important questions about God, racial segregation, and issues surrounding the hearing impaired with a light and thoughtful touch.a a"Publishers Weekly" Jacqueline Woodson (www.jacquelinewoodson.com)xa0is the recipient of a 2020 MacArthur Fellowship, the 2020 Hans Christian Andersen Award, the 2018 Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, and the 2018 Children’s Literature Legacy Award. Shexa0was the 2018–2019 National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, and in 2015, she was named the Young People’s Poet Laureate by the Poetry Foundation. She received the 2014 National Book Award for her New York Times bestselling memoir Brown Girl Dreaming , which was also a recipient of the Coretta Scott King Award, a Newbery Honor, the NAACP Image Award, and a Sibert Honor. She wrote the adult books Red at the Bone , a New York Times bestseller, and Another Brooklyn , a 2016 National Book Award finalist.xa0Born in Columbus, Ohio, Jacqueline grew up in Greenville, South Carolina, and Brooklyn, New York, and graduated from college with a B.A. in English. She is the author of dozens of award-winning books for young adults, middle graders, and children; among her many accolades, she is a four-time Newbery Honor winner, a four-time National Book Award finalist, and a three-time Coretta Scott King Award winner. Her books include Coretta Scott King Award winner Before the Ever After; New York Times bestsellers The Day You Begin and Harbor Me ; The Other Side , Each Kindness , Caldecott Honor book Coming On Home Soon ; Newbery Honor winners Feathers , Show Way , and After Tupac and D Foster ; and Miracle's Boys , which received the LA Times Book Prize and the Coretta Scott King Award. Jacqueline is also a recipient of the Margaret A. Edwards Award for lifetime achievement for her contributions to young adult literature and a two-time winner of the Jane Addams Children's Book Award. She lives with her family in Brooklyn, New York. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Title Page Copyright Page Dedication PART ONE Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 PART TWO Chapter 5 Chapter 6 PART THREE Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 PART FOUR Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Acknowledgements Discussion Questions An Exciting Preview of : Brown Girl Dreaming An Exciting Preview of : Peace, Locomotion PUFFIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin GroupPenguin Young Readers Group, 345 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, EnglandPenguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, IndiaPenguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Registered Offices: Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published in the United States of America by G. P. Putnam’s Sons,a division of Penguin Young Readers Group, 2007Published by Puffin Books, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group, 2009 Copyright © Jacqueline Woodson, 2007All rights reserved THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS EDITION AS FOLLOWS:Woodson, Jacqueline.Feathers / Jacqueline Woodson.p. cm. ISBN: 9781101019832 ISBN: 9781101019832 The publisher does not have any control over and does not assumeany responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content. for Juliet Hope is the thing with feathersthat perches in the soul,And sings the tune—without the words,And never stops at all —EMILY DICKINSON PART ONE 1 His coming into our classroom that morning was the only new thing. Everything else was the same way it’d always been. The snow coming down. Ms. Johnson looking out the window, then after a moment, nodding. The class cheering because she was going to let us go out into the school yard at lunchtime. It had been that way for days and days. And then, just before the lunch bell rang, he walked into our classroom. Stepped through that door white and softly as the snow. The class got quiet and the boy reached into his pocket and pulled something out. A note for you, Ms. Johnson, the boy said. And the way his voice sounded, all new and soft in the room, made most of the class laugh out loud. But Ms. Johnson gave us a look and the class got quiet. Now isn’t this the strangest thing, I thought, watching the boy. Just that morning I’d been thinking about the year I’d missed a whole month of school, showing up in late October after everybody had already buddied up. I’d woken up with that thought and, all morning long, hadn’t been able to shake it. The boy was pale and his hair was long—almost to his back. And curly—like my own brother’s hair but Mama would never let Sean’s hair grow that long. I sat at my desk, staring at his hair, wondering what a kid like that was doing in our school—with that long, curly hair and white skin and all. And he was skinny too. Tall and skinny with white, white hands hanging down below his coat sleeves. Skinny white neck showing above his collar. Brown corduroy bell-bottoms like the ones I was wearing. Not a pair of gloves in sight, just a beat-up dark green book bag that looked like it had a million things in it hanging heavy from his shoulder. Ms. Johnson said, “Welcome to our sixth-grade classroom,” and the boy looked up at her and smiled. Trevor was sitting in the row in front of me, and when the boy smiled, he coughed but the cough was trying to cover up a word that we weren’t allowed to say. Ms. Johnson shot him a look and Trevor just shrugged and tapped his pencil on his desk like he was tapping out a beat in his head. The boy looked at Trevor and Trevor coughed the word again but softer this time. Still, Ms. Johnson heard it. “You have one more chance, Mr. Trevor,” Ms. Johnson said, opening her attendance book and writing something in it with her red pen. Trevor glared at the boy but didn’t say the word again. The boy stared back at him—his face pale and calm and quiet. I had never seen such a calm look on a kid. Grown-ups could look that way sometimes, but not the kids I knew. The boy’s eyes moved slowly around the classroom but his head stayed still. It felt like he was seeing all of us, taking us in and figuring us out. When his eyes got to me, I made a face, but he just smiled a tiny, calm smile and then his eyes moved on. I looked down at my notebook. Beneath my name, I had written the date—Wednesday, January 6, 1971. The day before, Ms. Johnson had read us a poem about hope getting inside you and never stopping. I had written that part of the poem down— Hope is the thing with feathers —because I had loved the sound of it. Loved the way the words seemed to float across my notebook. When I told Mama about the poem, she’d said, Welcome to the seventies, Frannie. Sounds like Ms. Johnson’s trying to tell you all something about looking forward instead of back all the time. I just stared at Mama. The poem was about hope and how hope had these feathers on it. It didn’t have a single thing to do with looking forward or back or even sideways. But then Sean came home and I told him about the poem and the crazy thing Mama had said. Sean smiled and shook his head. You’re a fool, he signed to me. The word doesn’t have feathers. It’s a metaphor. Don’t you learn anything at Price? So maybe the seventies is the thing with feathers. Maybe it was about hope and moving forward and not looking behind you. Some days, I tried to understand all that grown-up stuff. But a lot of it still didn’t make any sense to me. When I looked up from my notebook, Ms. Johnson had assigned the boy a seat close to the front of the room, and when he sat down, I heard him let out a sigh. Something about the way the new boy sat there, with his shoulders all slumped and his head bent down, made me blink hard. The sadness came on fast. I tried to think of something different, the Christmas that had just passed and the presents I’d gotten. Mama’s face when Daddy leaned across the couch to hug her tight. My older brother, Sean, holding up a basketball jersey and signing, I forgot I told you I wanted this! His face all broken out into a grin, his hands flying through the air. I put the picture of the sign for forgot in my head—four fingers sliding across the forehead like they’re wiping away a thought. Sometimes the signs took me to a different thinking place. The bell rang and Ms. Johnson said, “I’ll do a formal introduction after lunch.” All of us got up at the same time and stood in two straight lines, girls on one side, boys on the other. Ms. Johnson led us out of the classroom and down the hall toward the cafeteria. As usual, Rayray acted the fool, doing some crazy dance steps and a quick half-split when Ms. Johnson wasn’t looking. Trevor turned to the boy and whispered, “Don’t no pale-faces go to this school. You need to get your white butt back across the highway.” “I know I don’t hear anyone talking behind me,” Ms. Johnson said before the boy could say anything back. But the boy just stared at Trevor as we walked. Even after, when Trevor turned back around, the boy continued looking. “Face forward, Frannie,” Ms. Johnson said. I turned forward. “You’re just as pale as I am . . . my brother,” I heard the boy say. When I turned around again, the boy was looking at Trevor, his face still calm even though the words he’d just spoken were hanging in the air. Trevor took a deep breath, but before he could turn around again, Ms. Johnson did. She looked at the boy and raised her eyebrows. “We don’t talk while we’re on line,” she said. “Do we?” “No, Ms. Johnson,” the whole class said. When Rayray saw how mad Trevor was getting, he looked scared. When he saw me watching him, he pointed to the boy and pulled his finger across his neck. “If I have to ask you to turn around again, Frannie, I’m pulling you up here with me.” I faced forward again. Trevor was light, lighter than most of the other kids who went to our school, and blue-eyed. On the first day of school, Rayray made the mistake of asking him if he was part white and Trevor hit him. Hard. After that, nobody asked that question anymore. But I had heard Mama and a neighbor talking about Trevor’s daddy, how he was a white man who lived across the highway. And for a while, there were lots of kids at school whispering. But nobody said anything to Trevor. As the months passed and he kept getting in trouble for hitting people, we figured out that he had a mean streak in him—one minute he’d be smiling, the next his blue eyes would get all small and he’d be ramming himself into somebody who’d said the wrong thing or given him the wrong look. Sometimes, he’d just sneak up behind a person and slap the back of their head—for no reason. The whole class was a little bit afraid of him, but Rayray was a lot afraid. As we walked down the hall, I stared at Trevor’s back, wondering how long the boy would have to wait before he got his head slapped. 2 I could smell burgers and French fries in the cafeteria. Mr. Hungry was hollering loud in my stomach, so I didn’t think anything else about the boy until he showed up on the lunch line in front of me. I watched him take a fish sandwich, French fries and chocolate pudding. The fish sandwiches were for the kids that didn’t like burgers and usually, at the end of lunch period, there were a whole lot of fish sandwiches left. I wrinkled my nose at his tray and tried to grab two burgers. “You know the rules, Frannie,” Miss Costa, the lunch lady, said. “Come back when you’re done with the first one.” “I was just trying to save myself a trip,” I said, putting a burger back. The boy looked over his shoulder and smiled at me again. Then he went and sat over in the corner, under the loudspeaker. I sat down across from Maribel Tanks only because it was right next to Samantha. “Have you lost your mind,” I whispered to Samantha. Samantha just looked at me with one of her eyebrows raised and I knew she was thinking what she was always saying, which was I’m not the one that doesn’t like Maribel—that’s you. Me and Samantha went back to first grade together. One day, I was just this little kid alone in the first grade, coming into class a month after everyone. For a whole week, I didn’t have a single friend. And then, the next week, there was Samantha walking over to me, saying, “Do you want to play?” Even though we weren’t the kind of friends that always spent every single second together and dressed alike and stuff like that, we hung real tight at school. Me and Maribel never played. We hardly even talked. She had gone to private school and then, in fourth grade, that school closed, and since her parents didn’t want to send her across the highway for private school, she came to Price. But, to hear her tell it, you’d think she was still in some high and mighty private school—always finding some kind of way to drop it into a conversation, always wrinkling her nose at me like she couldn’t even believe we had to share the same air. I looked over at the boy. He had his head bent over his food like he was praying. Read more

Features & Highlights

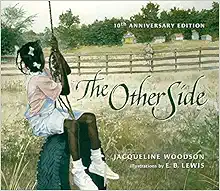

- A Newbery Honor BookA beautiful and moving novel from a three-time Newbery Honor-winning author

- “Hope is the thing with feathers” starts the poem Frannie is reading in school. Frannie hasn’t thought much about hope. There are so many other things to think about. Each day, her friend Samantha seems a bit more “holy.” There is a new boy in class everyone is calling the Jesus Boy. And although the new boy looks like a white kid, he says he’s not white. Who is he?

- During a winter full of surprises, good and bad, Frannie starts seeing a lot of things in a new light—her brother Sean’s deafness, her mother’s fear, the class bully’s anger, her best friend’s faith and her own desire for “the thing with feathers.”

- Jacqueline Woodson once again takes readers on a journey into a young girl’s heart and reveals the pain and the joy of learning to look beneath the surface.

- "[Frannie] is a wonderful role model for coming of age in a thoughtful way, and the book offers to teach us all about holding on to hope."—

- Children's Literature

- "A wonderful and necessary purchase for public and school libraries alike."—

- VOYA