Description

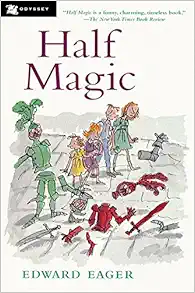

“Half Magic is a funny, charming, timeless book, as much a pleasure to read to a child now as it was forty years ago. Those who had it read to them then may even have an obligation to pass on the pleasure.”—The New York Times Book Review Edward Eager (1911–1964) worked primarily as a playwright and lyricist. It wasn’t until 1951, while searching for books to read to his young son, Fritz, that he began writing children’s stories. His classic Tales of Magic series started with the best-selling Half Magic, published in 1954. In each of his books he carefully acknowledges his indebtedness to E. Nesbit, whom he considered the best children’s writer of all time—“so that any child who likes my books and doesn’t know hers may be led back to the master of us all.” Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. 1. How It BeganIt began one day in summer about thirty years ago, and it happened to four children. Jane was the oldest and Mark was the only boy, and between them they ran everything. Katharine was the middle girl, of docile disposition and a comfort to her mother. She knew she was a comfort, and docile, because she'd heard her mother say so. And the others knew she was, too, by now, because ever since that day Katharine would keep boasting about what a comfort she was, and how docile, until Jane declared she would utter a piercing shriek and fall over dead if she heard another word about it. This will give you some idea of what Jane and Katharine were like. Martha was the youngest, and very difficult. The children never went to the country or a lake in the summer, the way their friends did, because their father was dead and their mother worked very hard on the other newspaper, the one almost nobody on the block took. A woman named Miss Bick came in every day to care for the children, but she couldn't seem to care for them very much, nor they for her. And she wouldn't take them to the country or a lake; she said it was too much to expect and the sound of waves affected her heart. "Clear Lake isn't the ocean; you can hardly hear it," Jane told her. "It would attract lightning," Miss Bick said, which Jane thought cowardly, besides being unfair arguing. If you're going to argue, and Jane usually was, you want people to line up all their objections at a time; then you can knock them all down at once. But Miss Bick was always sly. Still, even without the country or a lake, the summer was a fine thing, particularly when you were at the beginning of it, looking ahead into it. There would be months of beautifully long, empty days, and each other to play with, and the books from the library. In the summer you could take out ten books at a time, instead of three, and keep them a month, instead of two weeks. Of course you could take only four of the fiction books, which were the best, but Jane liked plays and they were nonfiction, and Katharine liked poetry and that was nonfiction, and Martha was still the age for picture books, and they didn't count as fiction but were often nearly as good. Mark hadn't found out yet what kind of nonfiction he liked, but he was still trying. Each month he would carry home his ten books and read the four good fiction ones in the first four days, and then read one page each from the other six, and then give up. Next month he would take them back and try again. The nonfiction books he tried were mostly called things like "When I Was a Boy in Greece," or "Happy Days on the Prairie"-things that made them sound like stories, only they weren't. They made Mark furious. "It's being made to learn things not on purpose. It's unfair," he said. "It's sly." Unfairness and slyness the four children hated above all. The library was two miles away, and walking there with a lot of heavy, already-read books was dull, but coming home was splendid-walking slowly, stopping from time to time on different strange front steps, dipping into the different books. One day Katharine, the poetry lover, tried to read Evangeline out loud on the way home, and Martha sat right down on the sidewalk after seven blocks of it, and refused to go a step farther if she had to hear another word of it. That will tell you about Martha. After that Jane and Mark made a rule that nobody could read bits out loud and bother the others. But this summer the rule was changed. This summer the children had found some books by a writer named E. Nesbit, surely the most wonderful books in the world. They read every one that the library had, right away, except a book called The Enchanted Castle, which had been out. And now yesterday The Enchanted Castle had come in, and they took it out, and Jane, because she could read fastest and loudest, read it out loud all the way home, and when they got home she went on reading, and when their mother came home they hardly said a word to her, and when dinner was served they didn't notice a thing they ate. Bedtime came at the moment when the magic ring in the book changed from a ring of invisibility to a wishing ring. It was a terrible place to stop, but their mother had one of her strict moments; so stop they did. And so naturally they all woke up even earlier than usual this morning, and Jane started right in reading out loud and didn't stop till she got to the end of the last page. There was a contented silence when she closed the book, and then, after a little, it began to get discontented. Martha broke it, saying what they were all thinking. "Why don't things like that ever happen to us?" "Magic never happens, not really," said Mark, who was old enough to be sure about this. "How do you know?" asked Katharine, who was nearly as old as Mark, but not nearly so sure about anything. "Only in fairy stories." "It wasn't a fairy story. There weren't any dragons or witches or poor woodcutters, just real children like us!" They were all talking at once now. "They aren't like us. We're never in the country for the summer, and walk down strange roads and find castles!" "We never go to the seashore and meet mermaids and sand-fairies!" "Or go to our uncle's, and there's a magic garden!" "If the Nesbit children do stay in the city it's London, and that's interesting, and then they find phoenixes and magic carpets! Nothing like that ever happens here!" "There's Mrs. Hudson's house," Jane said. "That's a little like a castle." "There's the Miss Kings' garden." "We could pretend..." It was Martha who said this, and the others turned on her. "Beast!" "Spoilsport!" Because of course the only way pretending is any good is if you never say right out that that's what you're doing. Martha knew this perfectly well, but in her youth she sometimes forgot. So now Mark threw a pillow at her, and so did Jane and Katharine, and in the excitement that followed their mother woke up, and Miss Bick arrived and started giving orders, and "all was flotsam and jetsam," in the poetic words of Katharine. Two hours later, with breakfast eaten, Mother gone to work and the dishes done, the four children escaped at last, and came out into the sun. It was fine weather, warm and blue-skied and full of possibilities, and the day began well, with a glint of something metal in a crack in the sidewalk. "Dibs on the nickel," Jane said, and scooped it into her pocket with the rest of her allowance, still jingling there unspent. She would get round to thinking about spending it after the adventures of the morning. The adventures of the morning began with promise. Mrs. Hudson's house looked quite like an Enchanted Castle, with its stone wall around and iron dog on the lawn. But when Mark crawled into the peony bed and Jane stood on his shoulders and held Martha up to the kitchen window, all Martha saw was Mrs. Hudson mixing something in a bowl. "Eye of newt and toe of frog, probably," Katharine thought, but Martha said it looked more like simple one-egg cake. And then when one of the black ants that live in all peony beds bit Mark, and he dropped Jane and Martha with a crash, nothing happened except Mrs. Hudson's coming out and chasing them with a broom the way she always did, and saying she'd tell their mother. This didn't worry them much, because their mother always said it was Mrs. Hudson's own fault, that people who had trouble with children brought it on themselves, but it was boring. So then the children went farther down the street and looked at the Miss Kings' garden. Bees were humming pleasantly round the columbines, and there were Canterbury bells and purple foxgloves looking satisfactorily old-fashioned, and for a moment it seemed as though anything might happen. But then Miss Mamie King came out and told them that a dear little fairy lived in the biggest purple foxglove, and this wasn't the kind of talk the children wanted to hear at all. They stayed only long enough to be polite, before trooping dispiritedly back to sit on their own front steps. They sat there and couldn't think of anything exciting to do, and nothing went on happening, and it was then that Jane was so disgusted that she said right out loud she wished there'd be a fire! The other three looked shocked at hearing such wickedness, and then they looked more shocked at what they heard next. What they heard next was a fire siren! Fire trucks started tearing past-the engine, puffing out smoke the way it used to do in those days, the Chief's car, the hook and ladder, the Chemicals! Mark and Katharine and Martha looked at Jane, and Jane looked back at them with wild wonder in her eyes. Then they started running. The fire was eight blocks away, and it took them a long time to get there, because Martha wasn't allowed to cross streets by herself, and couldn't run fast yet, like the others; so they had to keep waiting for her to catch up, at all the corners. And when they finally reached the house where the trucks had stopped, it wasn't the house that was on fire. It was a playhouse in the backyard, the fanciest playhouse the children had ever seen, two stories high and with dormer windows. You all know what watching a fire is like, the glory of the flames streaming out through the windows, and the wonderful moment when the roof falls in, or even better if there's a tower and it falls through the roof. This playhouse did have a tower, and it fell through the roof most beautifully, with a crash and a shower of sparks. And the fact that it was a playhouse, and small like the children, made it seem even more like a special fire that was planned just for them. And the little girl the playhouse belonged to turned out to be an unmistakably spoiled and unpleasant type named Genevieve, with long golden curls that had probably never ... Read more

Features & Highlights

- Since

- Half Magic

- first hit bookshelves in 1954, Edward Eager’s tales of magic have become beloved classics. Now four cherished stories by Edward Eager about vacationing cousins who stumble into magical doings and whimsical adventures are available in updated hardcover and paperback formats. The original lively illustrations by N. M. Bodecker have been retained, but eye-catching new cover art by Kate Greenaway Medalist Quentin Blake gives these classics a fresh, contemporary look for a whole new generation.