Description

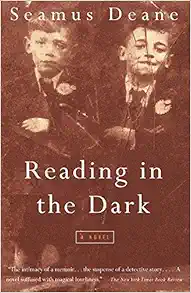

From the Inside Flap A New York Times Notable BookWinner of the Guardian Fiction PrizeWinner of the Irish Times Fiction Award and International Award"A swift and masterful transformation of family griefs and political violence into something at once rhapsodic and heartbreaking. If Issac Babel had been born in Derry, he might have written this sudden, brilliant book."--Seamus HeaneyHugely acclaimed in Great Britain, where it was awarded the Guardian Fiction Prize and short-listed for the Booker, Seamus Deane's first novel is a mesmerizing story of childhood set against the violence of Northern Ireland in the 1940s and 1950s.The boy narrator grows up haunted by a truth he both wants and does not want to discover. The matter: a deadly betrayal, unspoken and unspeakable, born of political enmity. As the boy listens through the silence that surrounds him, the truth spreads like a stain until it engulfs him and his family. And as he listens, and watches, the world of legend--the stone fort of Grianan, home of the warrior Fianna; the Field of the Disappeared, over which no gulls fly--reveals its transfixing reality. Meanwhile the real world of adulthood unfolds its secrets like a collection of folktales: the dead sister walking again; the lost uncle, Eddie, present on every page; the family house "as cunning and articulate as a labyrinth, closely designed, with someone sobbing at the heart of it."Seamus Deane has created a luminous tale about how childhood fear turns into fantasy and fantasy turns into fact. Breathtakingly sad but vibrant and unforgettable, Reading in the Dark is one of the finest books about growing up--in Ireland or anywhere--that has ever been written. A New York Times Notable BookWinner of the Guardian Fiction PrizeWinner of the Irish Times Fiction Award and International Award "A swift and masterful transformation of family griefs and political violence into something at once rhapsodic and heartbreaking. If Issac Babel had been born in Derry, he might have written this sudden, brilliant book."--Seamus Heaney Hugely acclaimed in Great Britain, where it was awarded the Guardian Fiction Prize and short-listed for the Booker, Seamus Deane's first novel is a mesmerizing story of childhood set against the violence of Northern Ireland in the 1940s and 1950s. The boy narrator grows up haunted by a truth he both wants and does not want to discover. The matter: a deadly betrayal, unspoken and unspeakable, born of political enmity. As the boy listens through the silence that surrounds him, the truth spreads like a stain until it engulfs him and his family. And as he listens, and watches, the world of legend--the stone fort of Grianan, home of the warrior Fianna; the Field of the Disappeared, over which no gulls fly--reveals its transfixing reality. Meanwhile the real world of adulthood unfolds its secrets like a collection of folktales: the dead sister walking again; the lost uncle, Eddie, present on every page; the family house "as cunning and articulate as a labyrinth, closely designed, with someone sobbing at the heart of it." Seamus Deane has created a luminous tale about how childhood fear turns into fantasy and fantasy turns into fact. Breathtakingly sad but vibrant and unforgettable, Reading in the Dark is one of the finest books about growing up--in Ireland or anywhere--that has ever been written. Seamus Deane was born in Derry in 1940. He is the author of a number of books of criticism and poetry, as well as the general editor of The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing. He currently teaches at the University of Notre Dame. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. chapter 1STAIRSFebruary 1945On the stairs, there was a clear, plain silence.It was a short staircase, fourteen steps in all, covered in lino from which the original pattern had been polished away to the point where it had the look of a faint memory. Eleven steps took you to the turn of the stairs where the cathedral and the sky always hung in the window frame. Three more steps took you on to the landing, about six feet long."Don't move," my mother said from the landing. "Don't cross that window."I was on the tenth step, she was on the landing. I could have touched her."There's something there between us. A shadow. Don't move.I had no intention. I was enthralled. But I could see no shadow."There's somebody there. Somebody unhappy. Go back down the stairs, son."I retreated one step. "How'll you get down?""I'll stay a while and it will go away.""How do you know?""I'll feel it gone.""What if it doesn't go?""It always does. I'll not be long."I stood there, looking up at her. I loved her then. She was small and anxious, but without real fear."I'm sure I could walk up there to you, in two skips.""No, no. God knows. It's bad enough me feeling it; I don't want you to as well.""I don't mind feeling it. It's a bit like the smell of damp clothes, isn't it?"She laughed. "No, nothing like that. Don't talk yourself into believing it. Just go downstairs."I went down, excited, and sat at the range with its red heart fire and black lead dust. We were haunted! We had a ghost, even in the middle of the afternoon. I heard her moving upstairs. The house was all cobweb tremors. No matter where I walked, it yielded before me and settled behind me. She came down after a bit, looking white."Did you see anything?""No, nothing, nothing at all. It's just your old mother with her nerves. All imagination. There's nothing there."I was up at the window before she could say anything more, but there was nothing there. I stared into the moiling darkness. I heard the clock in the bedroom clicking and the wind breathing through the chimney, and saw the neutral glimmer on the banister vanish into my hand as I slid my fingers down. Four steps before the kitchen door, I felt someone behind me and turned to see a darkness leaving the window.My mother was crying quietly at the fireside. I went in and sat on the floor beside her and stared into the redness locked behind the bars of the range.DISAPPEARANCESSeptember 1945People with green eyes were close to the fairies, we were told; they were just here for a little while, looking for a human child they could take away. If we ever met anyone with one green and one brown eye we were to cross ourselves, for that was a human child that had been taken over by the fairies. The brown eye was the sign it had been human. When it died, it would go into the fairy mounds that lay behind the Donegal mountains, not to heaven, purgatory, limbo or hell like the rest of us. These strange destinations excited me, especially when a priest came to the house of a dying person to give the last rites, the sacrament of Extreme Unction. That was to stop the person going to hell. Hell was a deep place. You fell into it, turning over and over in mid-air until the blackness sucked you into a great whirlpool of flames and you disappeared forever.My sister Eilis was the eldest of the children in the family. She was two years older than Liam; Liam was next, two years older than me. Then the others came in one-year or two-year steps-Gerard, Eamon, Una, Deirdre. Eilis and Liam brought me to Duffy's Circus with them to see the famous Bamboozelem, a magician who did a disappearing act. The tent was so high that the support poles seemed to converge in the darkness beyond the trapeze lights. From the shadow of the benches, standing against the base of one of the rope-wrapped poles, I watched him in his high boots, top hat, candystriped trousers ballooning over his waist, and a red tailcoat of satin which he flipped up behind him at the applause, so that it seemed he was suddenly on fire, and then, as the black top hat came up again, as though he was suddenly extinguished. He pulled jewels and cards and rings and rabbits out of the air, out of his mouth, pockets, ears. When everything had stopped disappearing, he smiled at us behind his great moustache, swelled his candystripe belly, tipped his top hat, flicked his coat of flame and disappeared in a cloud of smoke and a bang that made us jump a foot in the air. But his moustache remained, smiling the wrong way up in mid-air, where he had been.Everyone laughed and clapped. Then the moustache disappeared too. Everyone laughed harder. I stole a sidelong glance at Eilis and Liam. They were laughing. But were they at all sure of what had happened? Was Mr. Bamboozelem all right? I looked up into the darkness, half-fearing I would see his boots and candystriped belly sailing up into the dark beyond the trapeze lights. Liam laughed and called me an eedjit. "He went down a trapdoor," he said. "He's inside there," he said, pointing at the platform that was being wheeled out by two men while a clown traipsed forlornly after them, holding Mr. Bamboozelem's hat in his hand and brushing tears from his eyes. Everyone was laughing and clapping but I felt uneasy. How could they all be so sure?EDDIENovember 1947It was a fierce winter, that year. The snow covered the air-raid shelters. At night, from the stair window, the field was a white paradise of loneliness, and a starlit wind made the glass shake like loose, black water and the ice snore on the sill, while we slept, and the shadow watched.The boiler burst that winter, and the water pierced the fire from behind. It expired in a plume of smoke and angry hissings. It was desolate. No water, no heat, hardly any money, Christmas coming. My father called in my uncles, my mother's brothers, to help him fix it. Three came-Dan, Tom, John. Tom was the prosperous one; he was a building contractor, and employed the others. He had a gold tooth and curly hair and wore a suit. Dan was skinny and toothless, his face folded around his mouth. John had a smoker's hoarse, medical laugh. As they worked, they talked, telling story upon story, and I knelt on a chair at the table, rocking it back and forth, listening. They had stories of gamblers, drinkers, hard men, con men, champion bricklayers, boxing matches, footballers, policemen, priests, hauntings, exorcisms, political killings. There were great events they returned to over and over, like the night of the big shoot-out at the distillery between the IRA and the police, when Uncle Eddie disappeared. That was in April, 1922. Eddie was my father's brother.He had been seen years later in Chicago, said one.In Melbourne, said another.No, said Dan, he had died in the shoot-out, falling into the exploding vats of whiskey when the roof collapsed.Certainly he had never returned, although my father would not speak of it at all. The uncles always dwelt on this story for a while, as if waiting for him to respond or intervene to say something decisive. But he never did. He'd either get up and go out to get some coal, or else he'd turn the conversation as fast as he could. It was always a disappointment to me. I wanted him to make the story his own and cut in on their talk. But he always took a back seat in the conversation, especially on that topic.Then there was the story of the great exorcism that had, in one night, turned Father Browne's black hair white. The spirit belonged, they said, to a sailor whose wife had taken up with another man while he was away. On his return, she refused to live with him any more. So he took a room in the house opposite and stared across at his own former home every day, scarcely ever going out. Then he died. A week later, the lover was killed in a fall on the staircase. Within a year, the wife was found dead in the bedroom, a look of terror on her face. The windows of the house could not be opened and the staircase had a hot, rank smell that would lift the food from your stomach. Father Browne was the diocesan exorcist. When he was called in, they said, he tried four times before he could even get in the hall door, holding his crucifix before him and shouting in Latin. Once in, the great fight began. The house boomed as if it were made of tin. The priest outfaced the spirit on the stairs, driving it before him like a fading fire, and trapped it in the glass of the landing window. Then he dropped wax from a blessed candle on the snib. No one, he said, was ever to break that seal, which had to be renewed every month. And, he said, if anyone near death or in a state of mortal sin approached that window at night, they would see within it the stretched, enflamed face of a child in pain. It would sob and plead to be released from the devil that had entrapped it. But if the snib was broken open, the devil would enter the body of the person like a light, and that person would then be possessed and doomed forever.You could never be up to the devil.The boiler was fixed, and they went off-the great white winter piling up around the red fire again.ACCIDENTJune 1948One day the following summer I saw a boy from Blucher Street killed by a reversing lorry. He was standing at the rear wheel, ready to jump on the back when the lorry moved off. But the driver reversed suddenly, and the boy went under the wheel as the men at the street corner turned round and began shouting and running. It was too late. He lay there in the darkness under the truck, with his arm spread out and blood creeping out on all sides. The lorry driver collapsed, and the boy's mother appeared and looked and looked and then suddenly sat down as people came to stand in front of her and hide the awful sight.I was standing on the parapet wall above Meenan's Park, only twenty yards away, and I could see the police car coming up the road from the barracks at the far end. Two policemen got out, and one of them bent down and looked under the lorry. He stood up and pushed his cap back on his head and rubbed his hands on his thighs. I think he felt sick. His distress reached me, airborne, like a smell; in a small vertigo, I sat down on the wall. The lorry seemed to lurch again. The second policeman had a notebook in his hand and he went round to each of the men who had been standing at the corner when it happened. They all turned their backs on him. Then the ambulance came.For months, I kept seeing the lorry reversing, and Rory Hannaway's arm going out as he was wound under. Somebody told me that one of the policemen had vomited on the other side of the lorry. I felt the vertigo again on hearing this and, with it, pity for the man. But this seemed wrong; everyone hated the police, told us to stay away from them, that they were a bad lot. So I said nothing, especially as I felt scarcely anything for Rory's mother or the lorry driver, both of whom I knew. No more than a year later, when we were hiding from police in a corn field after they had interrupted us chopping down a tree for the annual bonfire on the fifteenth of August, the Feast of the Assumption, Danny Green told me in detail how young Hannaway had been run over by a police car which had not even stopped. "Bastards," he said, shining the blade of his axe with wet grass. I tightened the hauling rope round my waist and said nothing; somehow this allayed the subtle sense of treachery I had felt from the start. As a result, I began to feel then a real sorrow for Rory's mother and for the driver who had never worked since. The yellow-green corn whistled as the police car slid past on the road below. It was dark before we brought the tree in, combing the back lanes clean with its nervous branches.FEETSeptember 1948The plastic tablecloth hung so far down that I could only see their feet. But I could hear the noise and some of the talk, although I was so crunched up that I could make out very little of what they were saying. Besides, our collie dog, Smoky, was whimpering; every time he quivered under his fur, I became deaf to their words and alert to their noise.Smoky had found me under the table when the room filled with feet, standing at all angles, and he sloped through them and came to huddle himself on me. He felt the dread too. Una. My younger sister, Una. She was going to die after they took her to the hospital. I could hear the clumping of the feet of the ambulance men as they tried to manoeuvre her on a stretcher down the stairs. They would have to lift it high over the banister; the turn was too narrow. I had seen the red handles of the stretcher when the glossy shoes of the ambulance men appeared in the centre of the room. One had been holding it, folded up, perpendicular, with the handles on the ground beside his shiny black shoes, which had a tiny redness in one toecap when he put the stretcher handles on to the linoleum. The lino itself was so polished that there were answering rednesses in it too, buried upside down under the surface. That morning, Una had been so hot that, pale and sweaty as she was, she had made me think of sunken fires like these. Her eyes shone with pain and pressure, inflated from the inside.This was a new illness. I loved the names of the others-diphtheria, scarlet fever or scarlatina, rubella, polio, influenza; they made me think of Italian football players or racing drivers or opera singers. Each had its own smell, especially diphtheria: the disinfected sheets that hung over the bedroom doors billowed out their acrid fragrances in the draughts that chilled your ankles on the stairs. The mumps, which came after the diphtheria, wasn't frightening; it couldn't be: the word was funny and everybody's face was swollen and looked as if it had been in a terrific fight. But this was a new sickness. Meningitis. It was a word you had to bite on to say it. It had a fright and a hiss in it. When I said it I could feel Una's eyes widening all the time and getting lighter as if helium were pumping into them from her brain. They would burst, I thought, unless they could find a way of getting all that pure helium pain out. Read more

Features & Highlights

- A

- New York Times

- Notable BookWinner of the

- Guardian

- Fiction PrizeWinner of the

- Irish Times

- Fiction Award and International Award"A swift and masterful transformation of family griefs and political violence into something at once rhapsodic and heartbreaking. If Issac Babel had been born in Derry, he might have written this sudden, brilliant book."--Seamus HeaneyHugely acclaimed in Great Britain, where it was awarded the Guardian Fiction Prize and short-listed for the Booker, Seamus Deane's first novel is a mesmerizing story of childhood set against the violence of Northern Ireland in the 1940s and 1950s.The boy narrator grows up haunted by a truth he both wants and does not want to discover. The matter: a deadly betrayal, unspoken and unspeakable, born of political enmity. As the boy listens through the silence that surrounds him, the truth spreads like a stain until it engulfs him and his family. And as he listens, and watches, the world of legend--the stone fort of Grianan, home of the warrior Fianna; the Field of the Disappeared, over which no gulls fly--reveals its transfixing reality. Meanwhile the real world of adulthood unfolds its secrets like a collection of folktales: the dead sister walking again; the lost uncle, Eddie, present on every page; the family house "as cunning and articulate as a labyrinth, closely designed, with someone sobbing at the heart of it."Seamus Deane has created a luminous tale about how childhood fear turns into fantasy and fantasy turns into fact. Breathtakingly sad but vibrant and unforgettable,

- Reading in the Dark

- is one of the finest books about growing up--in Ireland or anywhere--that has ever been written.