Description

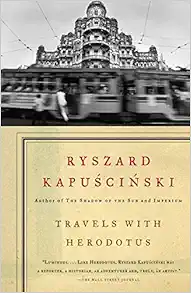

“Luminous. . . . Like Herodotus, Ryszard Kapuscinski was a reporter, a historian, an adventurer and, truly, an artist.” — The Wall Street Journal “Enchanting. . . . Underneath its shimmering prose beats the unquiet heart of a fundamentally decent man and an uncommonly gifted observer. . . . It has a startling clarity and power.” — The New Republic “A work of art: so eloquent, so simple, that you find yourself marveling at its prose….a travel book that all students of writing and of literature ought to read.” — The Washington Post Book World Ryszard Kapuscinski , Poland's most celebrated foreign correspondent, was born in 1932. After graduating with a degree in history from Warsaw University, he was sent to India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan to report for the Polish news, which began his lifelong fascination with the Third World. During his four decades reporting on Asia, Latin America, and Africa, he befriended Che Guevara, Salvador Allende, and Patrice Lumumba; witnessed twentyseven coups and revolutions; and was sentenced to death four times. He died in 2007.His earlier books-- Shah of Shahs, The Emperor, Imperium, Another Day of Life, The Soccer War, and Shadow of the Sun --have been translated into nineteen languages. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. CROSSING THE BORDERBefore Herodotus sets out on his travels, ascending rocky paths, sailing a ship over the seas, riding on horseback through the wilds of Asia; before he happens upon the mistrustful Scythians, discovers the wonders of Babylon, and plumbs the mysteries of the Nile; before he experiences a hundred different places and sees a thousand inconceivable things, he will appear for a moment in a lecture on ancient Greece, which Professor Biezunska-Malowist delivers twice weekly to the first-year students in Warsaw University's department of history.He will appear and just as quickly vanish.He will disappear so completely that now, years later, when I look through my notes from those classes, I do not find his name. There are Aeschylus and Pericles, Sappho and Socrates, Heraclitus and Plato; but no Herodotus. And yet we took such careful notes. They were our only source of information. The war had ended six years earlier, and the city lay in ruins. Libraries had gone up in flames, we had no textbooks, no books at all to speak of.The professor has a calm, soft, even voice. Her dark, attentive eyes regard us through thick lenses with marked curiosity. Sitting at a high lectern, she has before her a hundred young people the majority of whom have no idea that Solon was great, do not know the cause of Antigone's despair, and could not explain how Themistocles lured the Persians into a trap.If truth be told, we didn't even quite know where Greece was or, for that matter, that a contemporary country by that name had a past so remarkable and extraordinary as to merit studying at university. We were children of war. High schools were closed during the war years, and although in the larger cities clandestine classes were occasionally convened, here, in this lecture hall, sat mostly girls and boys from remote villages and small towns, ill read, undereducated. It was 1951. University admissions were granted without entrance examinations, family provenance mattering most--in the communist state the children of workers and peasants had the best chances of getting in.The benches were long, meant for several students, but they were still too few and so we sat crowded together. To my left was Z.--a taciturn peasant from a village near Radomsko, the kind of place where, as he once told me, a household would keep a piece of dried kielbasa as medicine: if an infant fell ill, it would be given the kielbasa to suck. "Did that help?" I asked, skeptically. "Of course," he replied with conviction and fell into gloomy silence again. To my right sat skinny W., with his emaciated, pockmarked face. He moaned with pain whenever the weather changed; he said he had taken a bullet in the knee during a forest battle. But who was fighting against whom, and exactly who shot him, this he would not say. There were also several students from better families among us. They were neatly attired, had nicer clothes, and the girls wore high heels. Yet they were striking exceptions, rare occurrences--the poor, uncouth countryside predominated: wrinkled coats from army surplus, patched sweaters, percale dresses.The professor showed us photographs of antique sculptures and of Greek figures painted on brown vases--beautiful, statuesque bodies, noble, elongated faces with fine features. They belonged to some unknown, mythic universe, a world of sun and silver, warm and full of light, populated by slender heroes and dancing nymphs. We didn't know what to make of it. Looking at the photographs, Z. was morosely silent and W. contorted himself to massage his aching knee. Others looked on, attentive yet indifferent. Before those future prophets proclaiming the clash of civilizations, the collision was taking place long ago, twice a week, in the lecture hall where I learned that there once lived a Greek named Herodotus.I knew nothing as yet of his life, or about the fact that he left us a famous book. We would in any event have been unable to read The Histories, because at that moment its Polish translation was locked away in a closet. In the mid-1940s The Histories had been translated by Professor Seweryn Hammer, who deposited his manuscript in the Czytelnik publishing house. I was unable to ascertain the details because all the documentation disappeared, but it happens that Hammer's text was sent by the publisher to the typesetter in the fall of 1951. Barring any complications, the book should have appeared in 1952, in time to find its way into our hands while we were still studying ancient history. But that's not what happened, because the printing was suddenly halted. Who gave the order? Probably the censor, but it's impossible to know for certain. Suffice it to say that the book finally did not go to press until three years later, at the end of 1954, arriving in the bookstores in 1955.One can speculate about the delay in the publication of The Histories. It coincides with the period preceding the death of Stalin and the time immediately following it. The Herodotus manuscript arrived at the press just as Western radio stations began speaking of Stalin's serious illness. The details were murky, but people were afraid of a new wave of terror and preferred to lie low, to risk nothing, to give no one any pretext, to wait things out. The atmosphere was tense. The censors redoubled their vigilance.But Herodotus? A book written two and a half thousand years ago? Well, yes: because all our thinking, our looking and reading, was governed during those years by an obsession with allusion. Each word brought another one to mind; each had a double meaning, a false bottom, a hidden significance; each contained something secretly encoded, cunningly concealed. Nothing was ever plain, literal, unambiguous--from behind every gesture and word peered some referential sign, gazed a meaningfully winking eye. The man who wrote had difficulty communicating with the man who read, not only because the censor could confiscate the text en route, but also because, when the text finally reached him, the latter read something utterly different from what was clearly written, constantly asking himself: What did this author really want to tell me?And so a person consumed, obsessively tormented by allusion reaches for Herodotus. How many allusions he will find there! The Histories consists of nine books, and each one is allusions heaped upon allusions. Let us say he opens, quite by accident, Book Five. He opens it, reads, and learns that in Corinth, after thirty years of bloodthirsty rule, the tyrant called Cypselus died and was succeeded by his son, Periander, who would in time turn out to be even more bloodthirsty than his father. This Periander, when he was still a dictator-in-training, wanted to learn how to stay in power, and so sent a messenger to the dictator of Miletus, old Thrasybulus, asking him for advice on how best to keep a people in slavish fear and subjugation.Thrasybulus, writes Herodotus, took the man sent by Periander out of the city and into a field where there were crops growing. As he walked through the grain, he kept questioning the messenger and getting him to repeat over and over again what he had come from Corinth to ask. Meanwhile, every time he saw an ear of grain standing higher than the rest, he broke it off and threw it away, and he went on doing this until he had destroyed the choicest, tallest stems in the crop. After this walk across the field, Thrasybulus sent Periander's man back home, without having offered him any advice. When the man got back to Corinth, Periander was eager to hear Thrasybulus' recommendations, but the agent said that he had not made any at all. In fact, he said, he was surprised that Periander had sent him to a man of that kind--a lunatic who destroyed his own property--and he described what he had seen Thrasybulus doing.Periander, however, understood Thrasybulus' actions. He realized that he had been advising him to kill outstanding citizens, and from then on he treated his people with unremitting brutality. If Cypselus had left anything undone during his spell of slaughter and persecution, Periander finished the job.And gloomy, maniacally suspicious Cambyses? How many allusions, analogies, and parallels in this figure! Cambyses was the king of a great contemporary power, Persia. He ruled between 529 and 522 B.C.E.Everything goes to make me certain that Cambyses was completely mad . . . His first atrocity was to do away with his brother Smerdis . . . and the second was to do away with his sister, who had come with him to Egypt. She was also his wife, as well as being his full sister . . . [and] on another occasion he found twelve of the highest-ranking Persians guilty of a paltry misdemeanour and buried them alive up to their necks in the ground. . . . These are a few examples of the insanity of his behaviour towards the Persians and his allies. During his time in Memphis he even opened some ancient tombs and examined the corpses.Cambyses . . . set out to attack the Ethiopians, without having requisitioned supplies or considered the fact that he was intending to make an expedition to the ends of the earth . . . so enraged and insane that he just set off with all his land forces . . . However, they completely ran out of food before they had got a fifth of the way there, and then they ran out of yoke-animals as well, because they were all eaten up. Had Cambyses changed his mind when he saw what was happening, and turned back, he would have redeemed his original mistake by acting wisely; in fact, however, he paid no attention to the situation and continued to press on. As long as there were plants to scavenge, his men could stay alive by eating grass, but then they reached the sandy desert. At that point some of them did something dreadful: they cast lots to choose one in every ten men among them--and ate him. When Cambyses heard about this, fear of cannibalism made him abandon his expedition to Ethiopia and turn his men back.As I mentioned, Herodotus's opus appeared in the bookstores in 1955. Two years had passed since Stalin's death. The atmosphere became more relaxed, people breathed more freely. Ilya Ehrenburg's novel The Thaw had just appeared, its title lending itself to the new epoch just beginning. Literature seemed to be everything then. People looked to it for the strength to live, for guidance, for revelation.I completed my studies and began working at a newspaper. It was called Sztandar Mtodych (The Banner of Youth). I was a novice reporter and my beat was to follow the trail of letters sent to the editor back to their points of origin. The writers complained about injustice and poverty, about the fact that the state took their last cow or that their village was still without electricity. Censorship abated and one could write, for example, that in the village of Chodow there is a store but that its shelves are always bare and there is never anything to buy. Progress consisted of the fact that while Stalin was alive, one could not write that a store was empty--all of them had to be excellently stocked, bursting with wares. I rattled along from village to village, from town to town, in a hay cart or a rickety bus, for private cars were a rarity and even a bicycle wasn't easily to be had.My route sometimes took me to villages along the border. But this happened infrequently. For the closer one got to a border, the emptier grew the land and the fewer people one encountered. This emptiness increased the mystery of these regions. I was struck, too, by how silent the border zone was. This mystery and quiet attracted and intrigued me. I was tempted to see what lay beyond, on the other side. I wondered what one experiences when one crosses the border. What does one feel? What does one think? It must be a moment of great emotion, agitation, tension. What is it like, on the other side? It must certainly be--different. But what does "different" mean? What does it look like? What does it resemble? Maybe it resembles nothing that I know, and thus is inconceivable, unimaginable? And so my greatest desire, which gave me no peace, which tormented and tantalized me, was actually quite modest: I wanted one thing only--the moment, the act, the simple fact of crossing the border. To cross it and come right back--that, I thought, would be entirely sufficient, would satisfy my quite inexplicable yet acute psychological hunger.But how to do this? None of my friends from school or university had ever been abroad. Anyone with a contact in another country generally preferred not to advertise it. I was even cross with myself for this bizarre yen; still, it didn't abate for a moment.One day I encountered my editor in chief in the hallway. Irena Tarlowska was a strapping, handsome woman with thick blond hair parted to one side. She said something about my recent stories, and then asked me about my plans for the near future. I named various villages to which I would be going, the issues that awaited me there, and then summoned my courage and said: "One day, I would very much like to go abroad.""Abroad?" she said, surprised and slightly frightened, because in those days going abroad was no ordinary matter. "Where? What for?" she asked."I was thinking about Czechoslovakia," I answered. I wouldn't have dared to say something like Paris or London, and frankly they didn't really interest me; I couldn't even imagine them. This was only about crossing the border--somewhere. It made no difference which one, because what was important was not the destination, the goal, the end, but the almost mystical and transcendent act. Crossing the border.A year passed following that conversation. The telephone rang in our newsroom. The editor in chief was summoning me to her office. "You know," she said, as I stood before her desk, "we are sending you. You'll go to India."My first reaction was astonishment. And right after that, panic: I knew nothing about India. I feverishly searched my thoughts for some associations, images, names. Nothing. Zero. (The idea of an Indian trip originated in the fact that several months earlier Jawaharlal Nehru had visited Poland, the first premier of a non-Soviet-bloc country to do so. The first contacts were being established. My stories were to bring that distant land closer.)At the end of our conversation, during which I learned that I would indeed be going forth into the world, Tarlowska reached into a cabinet, took out a book, and handing it to me said: "Here, a present, for the road." Read more

Features & Highlights

- From the renowned journalist comes this intimate account of his years in the field, traveling for the first time beyond the Iron Curtain to India, China, Ethiopia, and other exotic locales.In the 1950s, Ryszard Kapuscinski finished university in Poland and became a foreign correspondent, hoping to go abroad – perhaps to Czechoslovakia. Instead, he was sent to India – the first stop on a decades-long tour of the world that took Kapuscinski from Iran to El Salvador, from Angola to Armenia. Revisiting his memories of traveling the globe with a copy of Herodotus'

- Histories

- in tow, Kapuscinski describes his awakening to the intricacies and idiosyncrasies of new environments, and how the words of the Greek historiographer helped shape his own view of an increasingly globalized world. Written with supreme eloquence and a constant eye to the global undercurrents that have shaped the last half-century,

- Travels with Herodotus

- is an exceptional chronicle of one man's journey across continents.