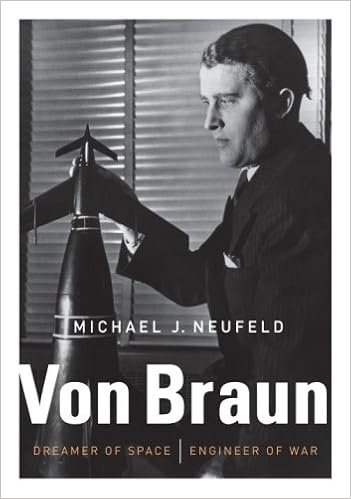

Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War

Hardcover – Deckle Edge, September 25, 2007

Description

From Publishers Weekly Neufeld, chair of the Space History Division at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum, offers what is likely to be the definitive biography of Wernher von Braun (1912–1977), the man behind both Nazi Germany's V-1 and V-2 rockets and America's postwar rocket program. Spearheading America's first satellite launch in 1958, which brought the U.S. up to par with the Soviet Union in space, von Braun was celebrated on the covers of Time and Life . Neufeld has a deep understanding of the technical and human challenges von Braun faced in leading the U.S. space program and lucidly explains his role in navigating the personal and public politics, management challenges and engineering problems that had to be solved before landing men on the moon. Neufield doesn't discount von Braun's past as an SS member and Nazi scientist (which was downplayed by NASA), but concludes nonjudgmentally that von Braun's lifelong obsession with becoming the Columbus of space, not Nazi sympathies, led him to his Faustian bargain to accept resources to build rockets regardless of their source or purpose. A wide range of readers (not only science and space buffs) will find this illuminating and rewarding. 16 pages of photos. (Sept. 26) Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. From Booklist *Starred Review* A historian of German rocket technology (The Rocket and the Reich, 1994), Neufeldxa0enters the populated field of von Braun biographies with, it is safe to say, the most comprehensively researched one. Only von Braun's relatives, it seems, have denied their stories to the author, whose documentary synthesis coversxa0the qualities that vaultedxa0von Braunxa0into technological leadership. Neufeld argues that von Braun's true distinction lay in organizational management. He could spot talent, motivate it with charisma, and persuade national leaders to fund his futuristic visions. That these leaders were initially those of Nazi Germany is the fulcrum of von Braun's life: Neufeld's account and assessment of von Braun's enmeshment in the Nazi system illustrates a progression arriving at party and SS membership, and involvement with forced labor. Letting readers mull the war-criminal question, Neufeld proceeds to the von Braun team's capture and transportation to the U.S. in 1945, von Braun's Christian conversion experience, and his fame in the 1950s and beyond as a space-flight proselytizer. Cautious in tone, Neufeld's judicious portrait of von Braun's outstanding qualities and his moral compromises promises toxa0become a space-history mainstay. Taylor, Gilbert "Neufeld's Von Braun surpasses all previous books about the man . . . Deeply researched, vigorously written, and balanced in its judgments." --Daniel J. Kevles, The Boston Globe "A serious, important book that does justice to its subject's moral complexity and place in history. It details what happened and why during the race to the moon." --M.G. Lord, Los Angeles Times Book Review "Neufeld catches von Braun in one ethically supine moment after another." --Thomas Mallon, The New Yorker "Neufeld has a deep understanding of the technical and human challenges von Braun faced in leading the U.S. space program and lucidly explains his role in navigating the personal and public politics, management challenges and engineering problems that had to be solved before landing men on the moon." -- Publishers Weekly "The defining work on a still-controversial figure." -- Kirkus "Neufeld's judicious portrait of von Braun's outstanding qualities and his moral compromises promises to become a space-history mainstay." -- Booklist Michael J. Neufeld is chair of the Space History Division of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. Born and raised in Canada, he received his doctorate in history from The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. His second book, The Rocket and the Reich: Peenemünde and the Coming of the Ballistic Missile Era , won the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics History Manuscript Award and the Society for the History of Technology Dexter Prize. He lives in Takoma Park, Maryland. From The Washington Post Reviewed by Guy Gugliotta Very early during his career in Hitler's Germany, Wernher von Braun understood the essential dilemma that confronted -- and in many ways still confronts -- almost anyone bewitched by the possibilities of rocketry and space: "I had no illusions whatsoever as to the tremendous amount of money necessary to convert the liquid-fuel rocket from [an] exciting toy . . . to a serious machine," he wrote. "To me, the Army's money was the only hope for big progress toward space travel." Von Braun from his youth dreamed of spaceships, but first he had to make a weapon, and he willingly built one, even knowing that he was using slave labor to do it. This Faustian bargain lies at the heart of space historian Michael J. Neufeld's carefully researched biography of von Braun, the Third Reich wunderkind who built the V-2, the world's first ballistic missile, then emigrated to the United States to design weapons and eventually to develop the epic Saturn V rocket that sent six sets of Apollo astronauts to the moon. In between, he managed, through charm, wit and undeniable genius, to become the charismatic spokesman for space travel in America -- a role that earned him admiration from young baby boomers who saw him on Walt Disney's "Tomorrowland" TV show and ridicule from such counterculture icons as singer Tom Lehrer: Don't say that he's hypocritical Say rather that he's apolitical. "Once the rockets are up, who cares where they come down? That's not my department," says Wernher von Braun. Today, 35 years after his death from cancer at a relatively young 65, von Braun remains as difficult to pigeonhole as ever -- at once the most influential rocket engineer of the 20th century and an ambitious charmer whose detractors dismiss him as an opportunist and war criminal. Neufeld, chair of space history at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum, navigates this minefield in an unusually measured fashion. Rather than picking a side and marshaling arguments, his journalistic approach lays out the evidence on both sides and invites readers to make their own judgments. Neufeld clearly is less than enamored of von Braun, yet gives due respect to his accomplishments. The reader who seeks closure will come away disappointed, but Neufeld intended it that way. Von Braun loved engineering and space from childhood. Also, he came from Germany's landowning aristocracy and had little difficulty offering unquestioning loyalty to an authoritarian government, even the Third Reich. Neufeld concedes that the precocious von Braun -- he was effectively in charge of rocket development at the age of 25 -- probably thought little at first about the pitfalls of serving Hitler, but if he had, it would not have bothered him. At certain points, von Braun could have dragged his feet, "but that would have required strong, unspoken moral and political convictions and a willingness to damage his career," Neufeld says. "Those were manifestly lacking." Neufeld writes with economy and dispatch, and the narrative moves quickly, particularly in the early going. Although von Braun's surviving German colleagues refused to grant interviews, Neufeld's mastery of available German material and memoirs, coupled with the records of post-World War II debriefings and the harrowing recollections of former French prisoners-of-war at the Nordhausen V-2 plant, give von Braun's German period a vivid immediacy. The book, however, frequently glosses over the engineering challenges faced by early rocketeers and the techniques and hardware developed by von Braun and others to resolve them. Aficionados will immediately notice this shortcoming, and even the uninitiated will occasionally wonder how seemingly intractable problems are suddenly overcome 10 pages later. Also missing are details about von Braun's personal life. The family has never granted interviews, and readers will be curious about his 1947 marriage, almost sight unseen, to his 18-year-old first cousin and his born-again conversion to evangelical Protestantism around the same time. The American half of von Braun's life will be more familiar to U.S. readers. Neufeld focuses considerable attention on von Braun's career as the U.S. space program's designated visionary, contrasting his public triumphs with continued but sporadic embarrassments about his Nazi past. Yet despite his career as a space pitchman, von Braun was no charlatan, and Neufeld shows clearly that his achievements as a rocketman are unsurpassed. He was able to put the first U.S. satellite, Explorer I, in orbit in the panicked aftermath of the Soviet Union's 1957 Sputnik launch, and he delivered the Saturn V in time to fulfill President John F. Kennedy's 1961 promise of putting a man on the Moon "before this decade is out." Von Braun may have been a flawed hero, as Neufeld elegantly shows, but he delivered the goods. Copyright 2007, The Washington Post. All Rights Reserved. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. Chapter One: The Wheel of Progress TO 1925 Demagoguery and democracy are brothers in etymology and spirit . . . for the German ear the word democracy awakens memories of complete chaos after the First [World] War. —MAGNUS FREIHERR VON BRAUN[1]When Wernher von Braun was about ten years old, his tall, elegant mother, Emmy Freifrau (Baroness) von Braun, asked him what he would like to do with his life. “I want to help turn the wheel of progress” was his answer, a response that sounded odd and surprising to her, coming out of the mouth of a small boy. An unusually abstract statement, it prefigured a lifetime of fascination with science and technology.[2]Equally surprising, it came from the mouth of a true son of the Junkers—the noble caste that had once dominated the Prussian civil service, officer corps, and landowning elite. Engineering and science were not careers that Junker sons often chose, even in the 1920s. It seemed to reflect some inner compulsion of Wernher’s, but it also reflected the tenor of the times—a time of dramatic technological and political change. He had been born in 1912, in a traditional prewar world; his massively built, mustachioed father, Magnus Freiherr von Braun, had been a rapidly ascending civil servant in the empire of Kaiser Wilhelm II, while his intellectually gifted mother was the orphaned daughter of an estate owner. Less than ten years later his father would be forced out of the civil service in the political turmoil of the new Weimar Republic. The family moved to the modern world city of Berlin. Yet as much of a maverick and a Berliner as Wernher von Braun would turn out to be, his Prussian Junker upbringing influenced his values, his abilities, and his choices—more so, in fact, than his father would later be willing to credit.Of his parents’ two families, the von Brauns and the von Quistorps, the former was of much older aristocratic stock. Magnus von Braun, who inherited from his father the hobby of genealogical research, eventually traced the male line back to 1285, although in all probability an ancestor had battled the Mongols at Liegnitz in 1241. The von Brauns arose from the soil of Silesia, a verdant and rolling province on both sides of the Oder River, east of the Czech heartland of Bohemia and Moravia. In 1573 the Holy Roman emperor elevated two of them to the rank of Reichsfreiherr (imperial baron) for their military accomplishments.[3]Magnus von Braun came, however, from an even more distant outpost of Germandom, East Prussia—a province that would disappear from the map in 1945, when Stalin divided it between the Soviet Union and Poland. In 1738 one descendant of the family, Gotthard Freiherr von Braun, entered Prussian service as a lieutenant in the garrison of the province’s capital city of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, Russia). There he married the daughter of a wealthy local burgher. His fifth child, Sigismund, also a Prussian officer, purchased the estate of Neucken, about thirty miles southwest of the city, in 1803 and erected a new house—Magnus von Braun’s ancestral home. One of the family’s close acquaintances in Königsberg had been the philosopher Immanuel Kant; the silver sugar spoon he gave to Sigismund as a wedding present was a holy object in the glass cabinet of the mansion, along with a golden snuffbox from Czar Alexander I of Russia. But in February 1807, not long after the house was finished, Napoleon fought the bloody and inconclusive Battle of Preussisch Eylau against the czar’s army around Neucken. Napoleon’s troops killed or stole all the farm animals, wrecked the estate buildings, and plundered the house, although valuables like Kant’s spoon were successfully carried away or hidden. It took the family years to recuperate economically from the damage—but the starvation and death inflicted on the estate’s enserfed peasantry were much worse.[4]On the seventy-first anniversary of the battle, 7 February 1878, a boy, Magnus Alexander Maximilian, was born at Neucken. His father was Lieutenant Colonel Maximilian Freiherr von Braun, who had inherited the estate in part because no fewer than three of his brothers, as Prussian officers, were killed in the 1866 war against Austria- Hungary. Military values and a fervent loyalty to the Hohenzollern kings of Prussia—who, after 1871, became emperors of the new, Prussian-dominated Germany—were the heart of the values taught on the estate. Magnus was the youngest of five; his brothers Friedrich (Fritz) and Siegfried both became army officers. While Fritz had to terminate his career to take over Neucken shortly before World War I because of the failing health of their father, Siegfried served all through the war, ending as colonel of the Third Guards Regiment. He was forced into other employment only because of the military’s drastic downsizing as a result of the Versailles Treaty.[5]Acceptable career choices for sons of the Prussian nobility were limited. Every able-bodied male was expected to at least serve a stint in the army before returning to estate agriculture, if there was a prospect of an inheritance—which in the nineteenth century was usually limited by primogeniture to the eldest son. Of course, a young man also had the possibility of marrying into an estate or, less often, accumulating enough wealth to buy one. As Prussia’s bureaucracy expanded from the eighteenth century on, however, the higher civil service and diplomatic corps opened up as employment possibilities for younger sons. Unlike the British aristocracy, all children of the Prussian aristocracy, male and female, inherited the father’s title, with the result that there were a lot of barons, countesses, and the like who usually lived well as a result of the privileges afforded them but had no landed property.Daughters in this very patriarchal society inevitably faced even more limited choices. Outside of marriage, about the only prospects they had were to remain with the family as a maiden aunt and sister, or to become a nurse or administrator in a church-based hospital or charity institution. As the Junkers (outside of parts of Silesia) were aggressively Lutheran, the option of taking holy orders was unavailable. Magnus von Braun’s oldest sibling, Magdalene (born 1865), remained at Neucken her whole life, whereas Adele eventually became the head of a children’s sanatorium on the Baltic coast of East Prussia. Neither ever married.[6]Old age often puts a nostalgic glow on one’s memories of childhood. Magnus von Braun’s memoirs, completed in American exile in the late 1940s and early 1950s, are no exception in that regard. He described Neucken as a patriarchal utopia: “the whole estate thought of itself as a large family. . . . Neighborly love . . . was natural and inevitable and at the same time Christian in nature. Patriarchal life on the land bound the people together into a tight community of fate.” The housing of Neucken’s laborers was, he conceded, “still primitive in my earliest youth,” but nonetheless it was better than the conditions he later witnessed in eastern Europe—not to mention those of blacks and Mexicans in Texas and Alabama. (Prussia had abolished serfdom in the early decades of the century, not necessarily to the benefit of the peasants, who often lost their land.) Raised in a stable, hierarchical, rural society in which dissent was rare, Magnus von Braun never saw any need to question a state of affairs in which the Junkers ran local government as their private preserve and most villages were wholly owned appendages of the estates. Indeed, his memoir forthrightly states his reactionary, monarchist, elitist politics—there had always been, and would always be, rulers and ruled; equality was unnatural. In the 1960s he told one of his grandsons, “This democracy thing is just a passing fad.”[7]Educated by a tutor at Neucken until the age of ten, he was then sent to Königsberg to receive the traditional elite education of the humanistic Gymnasium, with a heavy emphasis on languages—in the upper grades, a lot of Latin and Greek. He apparently showed some talent; after graduating on Easter 1896, he made his way to the old, venerable University of Göttingen in north-central Germany to study law, the mandatory path into the civil service. With his baronial title and with a healthy stipend from his father, Magnus was able to join an elite dueling fraternity, the Corps Saxonia, “which was made up almost exclusively of landed nobles.” In the old fraternity tradition, he did not study very hard but rather demonstrated his manliness by drinking and dueling. Graduating in spring 1899, he took his civil service entry exams in Königsberg and then did his one-year military service as an officer in the old Prussian royal city of Potsdam, outside Berlin. Again, his connections were the best: he entered the Hohenzollerns’ elite infantry regiment, the First Foot Guards. Kaiser Wilhelm II’s sons served in this regiment, and Magnus’s eldest brother, Fritz, was a captain in the Guards’ Rifle Battalion, which was responsible for the army’s first experiments with machine guns. Apparently the young Magnus made such a good impression that, when he finished his service in the fall of 1900, the officers of the regiment made him a reserve lieutenant. The rank and uniform, like the elite fraternity membership, were of great value in Imperial German society.[8]Returning to the civil service track, he then served the long, unpaid apprenticeship that led to the second exam and a permanent and paying position—a system designed to allow only the propertied access to the higher ranks. After serving in various places in eastern and western Prussia, he passed the assessor’s exam in 1905, although not with flying colors. But he showed initiative, a talent for dealing with peopl... Read more

Features & Highlights

- The first authoritative biography of Wernher von Braun, chief rocket engineer of the Third Reich—creator of the infamous V-2 rocket—who became one of the fathers of the U.S. space program. In this meticulously researched and vividly written life, Michael J. Neufeld gives us a man of profound moral complexities, glorified as a visionary and vilified as a war criminal, a man whose brilliance and charisma were coupled with an enormous and, some would say, blinding ambition.As one of the leading developers of rocket technology for the German army, von Braun yielded to pressure to join the Nazi Party in 1937 and reluctantly became an SS officer in 1940. During the war, he supervised work on the V-2s, which were assembled by starving slave laborers in a secret underground plant and then fired against London and Antwerp. Thousands of prisoners died—a fact he well knew and kept silent about for as long as possible.When the Allies overran Germany, von Braun and his team surrendered to the Americans. The U.S. Army immediately recognized his skills and brought him and his colleagues to America to work on the development of guided missiles, in a covert operation that became known as Project Paperclip. He helped launch the first American satellite in 1958 and headed NASA’s launch-vehicle development for the Apollo Moon landing.Handsome and likable, von Braun dedicated himself to selling the American public on interplanetary travel and became a household name in the 1950s, appearing on Disney TV shows and writing for popular magazines. But he never fully escaped his past, and in later years he faced increasing questions as his wartime actions slowly came to light.Based on new sources,

- Von Braun

- is a brilliantly nuanced portrait of a man caught between morality and progress, between his dreams of the heavens and the earthbound realities of his life.