Description

An Amazon Best Book of the Month, May 2014: When Orangette blogger and Bon Appétit columnist Molly Wizenberg emerged from the whirlwind of publishing her best-selling debut memoir, A Homemade Life , she was shocked to realize that her new husband Brandon’s latest ambitious/crazy scheme was coming to pass: with scant restaurant experience, he was opening a Brooklyn-style wood-fire pizza place in their Seattle neighborhood. Brandon and the restaurant were on the move, and she could give into their momentum or risk an unraveling marriage. In Delancey: A Man, A Woman, a Restaurant, a Marriage , we get Wizenberg's hilariously unvarnished, poignant account of how she found her place in their new life, and what it took both of them them--as well as the friends, relatives, and strangers-turned-friends who rallied to their aid--to transform an empty space into a community that feeds them, plus an expectant crowd that often snakes down the block (and occasionally feels like a zombie horde). If you have gauzy dreams of opening your own little place, you’ll glean essential lessons, like that you should really reconsider. But any fan of great food (especially pizza) will find much to love, including recipes for the meals they most enjoyed in the Delancey-opening era--food and cocktails that are improvisational, delicious, made memorable by time spent with excellent friends. Wizenberg finished her manuscript when she was 37-weeks pregnant with their daughter, June--“the heart of the pizza party”--and just as they opened bar-next-door Essex, events that we think call for another memoir. --Mari Malcolm From Booklist Marriage plus business isn’t always the best formula to produce happiness. Just ask author Wizenberg and her husband, Brandon Pettit. Armed with a lot of enthusiasm and youthful vigor, the two opened a Seattle pizzeria, determined to produce unique pies from fresh ingredients. A trained music composer, Brandon has multiple passions, including food and cooking. His zeal swept his wife along until, as owners of both a lease and an oven, they had to carry through with their dreams and actually hire staff, create a menu, and open the doors for paying customers. Despite the pizzeria’s success and her continued love for her husband, Wizenberg finds daily work stresses often overwhelming. Throughout the text, Wizenberg records recipes, not merely from the restaurant’s repertoire but from her own files of favorite foods. Anyone, married or not, considering launching a restaurant will take away from this memoir some valuable personal and professional lessons. --Mark Knoblauch "A crave-worthy memoir that is part love story, part restaurant industry tale. Scrumptious.” ― People "You'll feel the warmth from this pizza oven...affectionate...cheerfully honest...warm and inclusive, just like her cooking." ― USA Today "Wizenberg shines as a writer. She brilliantly turns the ups and downs of their do-it-yourself project into a compelling yet hilarious narrative....Like dipping into a lively, keenly observed diary....Charming." ― Boston Globe "Charming, funny, and honest--in a hip, understated way--Wizenberg combines simple, appealing recipes with a tale of how nurturing her husband's passion project helped her see him, and herself, more clearly." ― More "The messy, explosive, and exhilarating story of giving birth to a restaurant...draws readers right into the heat of the kitchen." ― Christian Science Monitor “When I sit down with Molly Wizenberg’s writing, it feels as though she’s just across the counter, coffee cup in hand, sharing an intimate truth….Inspiring, entertaining and informative, [Delancey] is a satisfying read.” ― Minneapolis Star Tribune "What makes this story so readable...is that it doesn't just chronicle the nuts and bolts of starting a restaurant. It's as much about navigating a new marriage, figuring out what kind of life you want to make together and what roles you want to play in life together." ― Dinner: A Love Story "Honest, humorous, and endearing." ― PopSugar "It's about how the things we make, make us . It's also about discovering our stories as we live them, learning to understand them, and ourselves through them. Oh, and it's about pizza too." ― Sweet Amandine "Illuminates the restaurant experience in a way that was entirely new to me....Molly's gift is to walk you through the process while simultaneously broadcasting her own emotional journey...honest and essential." ― Amateur Gourmet "You will cheer for Wizenberg...and her husband as they navigate the exciting and sometimes treacherous task of opening a Seattle pizza shop--and try to build a marriage too, in this honest, sprightly memoir." ― Coastal Living "Charming . . . humorous, intimate, and honest." ― Library Journal (starred review) "Fun and engaging." ― Publishers Weekly "Entertaining and wondering and plainspoken...full of the hard work and trial and error of emerging into adulthood." ― Bookforum "Molly Wizenberg writes with the sweet candor of Laurie Colwin and the sly amusement of M.F.K. Fisher. Delancey is the perfect restaurant tale -- gripping, nutty, and yet somehow meant to be." -- Amanda Hesser ― co-founder of Food52 and author of The Essential New York Times Cookbook "Delancey is so riveting, well-written, and interesting, I found myself wishing it were twice as long. Molly Wizenberg writes as well about life as she does about food. Her voice is so charming and funny and poignant, it made me want to invite myself over to her place for dinner, where I would certainly overstay. I loved this book." -- Kate Christensen ― author of Blue Plate Special: An Autobiography of My Appetites "You might think making pizza is a piece of cake (or pie!) But Molly Wizenberg’s tale of triumph as she and her husband learn to make the perfect pie, and construct the restaurant to serve it in, make for delicious – and dramatic – reading. Told with humility and humor, Delancey shows that with hard work and determination, dreams can come true . . . no matter what obstacles lie in your way." -- David Lebovitz ― author of My Paris Kitchen "Molly Wizenberg’s Delancey is so much more than a memoir about opening a highly regarded pizza restaurant. It is a story about building a marriage and a beloved community through grit, thrift, and self-determination in the pursuit of excellence. Ultimately this is a story about whole-heartedly embracing the one you love without trying to smooth away the rough edges or edit out the hard parts. It is also a most delicious read (with recipes!) that sent me to the kitchen as soon as I turned the final page." -- Susan Rebecca White ― author of A Place at the Table "Delancey is the extraordinary tale of what it means to build a life with the person you love, and the professional roller coaster ride that is opening and running a wildly successful restaurant together. Molly Wizenberg has, in her inimitable way, written a modern love story that marries razor-edged wit to warmth, and passion to flavor; Delancey is an utterly delicious read." -- Elissa Altman ― Poor Man's Feast Molly Wizenberg, winner of the 2015 James Beard Foundation Award, is the voice behind Orangette , named the best food blog in the world by the London Times . Her first book, A Homemade Life: Stories and Recipes from My Kitchen Table , was a New York Times bestseller, and her work has appeared in Bon Appétit , The Washington Post , The Art of Eating , and The Guardian , and on Saveur.com and Gourmet.com. She also cohosts the hit podcast Spilled Milk . She lives in Seattle with her husband Brandon Pettit, their daughter June, and two dogs named Jack and Alice. She and Brandon own and run the restaurants Delancey and Essex. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. Delancey 1 If you want to get Brandon’s family talking, you need only ask about his childhood tantrums, aaannnnnnnd they’re off! Their descriptions are sufficiently vivid that you’d think he’d had a screaming meltdown in the family car last week. But if you ask Brandon about his tantrums, he’ll tell you that he was constantly hungry, and that low blood sugar will bring out the wailing, shrieking lunatic in anyone. When he was eight or nine, he taught himself to cope by cooking. And his parents, who weren’t especially interested in cooking, rewarded his initiative, because in the Pettit household of Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, whoever cooked dinner didn’t have to do the cleanup afterward. Anyway, while most of his peers were off wrestling in the yard, breaking things, or lighting household pets on fire, Brandon got a lot of positive attention for cooking. His uncle Tom offered to teach him how to make a few dishes, and so did his mother’s friend Ellen. His best friend Steve’s mother, Laura, taught him how to make penne alla vodka when he was in middle school. Afterward, before he went home, she dumped out a small Poland Spring water bottle, refilled it with vodka, and gave it to him so that he could make the recipe for his parents. His mother found it in his backpack later that night, and you know how that story goes. Meanwhile, I grew up 1,500 miles to the west, in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, the only child in a family so preoccupied with cooking and eating that we would regularly spend dinner discussing what we might eat the following night. My parents met in Baltimore and courted over oysters and pan-fried shad roe, and though they had lived in the land of waving wheat and chicken-fried steak since a few years before I was born, they took pleasure in introducing me to lobster, croissants, and Dover sole. My father was a radiation oncologist, and he worked full-time until he was nearly seventy, but most evenings, after pouring himself a Scotch and thumbing absentmindedly through the mail, he made dinner. It wasn’t necessarily fancy—there were hamburgers and salad and cans of baked beans, and his macaroni and cheese involved a brick of Velveeta—but the kitchen was where he went to relax, to unwind from a day of seeing patients. He was a good cook. My mother is also a good cook, a very good cook, but I think of her mostly as a baker. She made brownies and crisps and birthday cakes, and in our neighborhood she became something of a legend for the elaborate cookies and candies she made each Christmas. Food was how the three of us spent time together. Cooking and eating gave our days their rhythm and consistency, and the kitchen was where everything happened. As a baby, I played on the floor with pots and spoons while my mother cooked. The three of us sat down to dinner at the kitchen table nearly every night (except Thursdays, when my parents went out and left me with a Stouffer’s Turkey Tetrazzini and Julia Beal, the elderly babysitter, who always arrived with a floral-patterned plastic bonnet tied under her chin), and we kept up the habit (minus Stouffer’s and Mrs. Beal, after a certain point) until I went to college. I started cooking with my parents when I was in high school. I was not what you would call a difficult teen: Friday night might find me baking a cake or holed up in my bedroom with my notebook of poems. If I felt like doing something really exciting, I might invite some friends over and make a rhubarb cobbler. When I was seventeen, Food Network came into existence, and then I spent hour after hour watching cooking shows, which fueled even more baking and a poem about immersing myself in a vat of Marshmallow Fluff. Brandon’s teenage years were a little more interesting—he regularly handed in his homework late—but he too watched a lot of cooking shows. This was back in the golden age when you could actually learn something from Food Network—when David Rosengarten’s brilliant Taste was still on the air and Emeril Lagasse’s show was taped on a modest set without a studio audience, live musicians, or abuse of the word bam. Brandon learned about extra virgin olive oil on Molto Mario and balsamic vinegar on Essence of Emeril and begged his parents to add them to the grocery list. He once watched a show about soups during which the host reeled off a number of tricks for adding flavor and body: add a Parmigiano-Reggiano rind or a bouquet garni, for example, or drop in a potato, toss in some dried mushrooms, or simmer a teabag in the stock. Armed with this information, he decided to combine all of the tricks in a single soup, surely the greatest soup the world would ever know. The result, he reports, was very flavorful, like runoff from a large-scale mining operation. Growing up, Brandon had four favorite pizza places: Posa Posa, Martio’s, and Michaelangelo’s, all in Nanuet, New York; and Kinchley’s, in Ramsey, New Jersey. Of course, every kid on earth loves pizza, and a lot of them probably have four favorite pizza joints. But I know of few eight-year-olds who want to interview the pizzaiolo. Brandon took dance classes as a kid, and the ballet studio was conveniently located a few doors down from Michaelangelo’s. After class, he would pummel the owner with questions. What’s in the dough? What do you put in the sauce? Why do you grate the mozzarella for the cheese pizza, instead of slicing it? In exchange for answers and free slices, he agreed to put coupons under the windshield wipers of cars in the parking lot out front. But if it were all really that straightforward, if Brandon and I had both homed in on food from the get-go, and if he had known that he would be a chef and I had known that I would someday own a restaurant with my chef husband, this would be a boring story, and I would not be telling it. Maybe even more than he loved to cook, Brandon loved to dance. His mother, wanting to expose her son to a little bit of everything, started him in dance classes as a very young kid, and by the time he was a preteen, he was on track to someday join a touring company. Down the line, he’d decided, he would be a choreographer. Choreography and cooking pushed the same buttons in him: they were both about making things, about taking a series of separate elements and assembling them in a particular sequence to make something appealing and new. As a middle schooler, he took upwards of eight hours of dance classes a week, and sometimes, depending on the season, he took as many as twenty. When he was twelve, he got into a prestigious summer program at the Pennsylvania Ballet school. Each afternoon, when he was supposed to be resting, he sneaked into the classes for older teens, where he got to partner with female dancers. This was the big time. One day, while doing some sort of move that you’re not supposed to do when you’re twelve, he fractured one of the vertebrae in his lower back. The upshot was that he couldn’t dance for the better part of a year, and as further punishment, he had to wear a plastic torso brace that made him look like Tom Hanks’s deranged secretary in Splash, the one who wore her bra over her clothes. He couldn’t do anything that required much mobility, but he could still cook. He could also practice the saxophone. In addition to dance, he’d taken music lessons—piano and saxophone—since he was a kid. Now, while sidelined from ballet, he began to practice for hours a day. After school, he’d go down to the basement, put on Pink Floyd’s “Money,” and play along, over and over, with the sax solo that starts at 2:04. Or he’d go to Tower Records and fish around in the discount bin for classic R&B and blues CDs, Charlie Parker or T-Bone Walker, and then he’d play along to those too. He sometimes went to the ballet studio to watch a class, to try to keep his head in it, but he began to notice that, maybe more than the physical movement itself, what he liked about dance was the music. Music was underneath all of it. By the time he started thinking about college, he was spending most of his non-school hours playing the saxophone, and when he wasn’t playing the saxophone, he was cooking. He thought about going to culinary school instead of college, but he’d been a vegetarian since birth—his parents, siblings, and most of his extended family are vegetarian—and while he didn’t want to cook meat, he also wasn’t interested in seeking out a specialized vegetarian culinary school, which seemed limiting in the long run. Anyway, he would always cook, he reasoned, whether or not he was a trained chef. He would always need to eat. But if he wanted to keep at his music, and if he wanted to go somewhere with it, he would need formal training. So he decided to try for a conservatory slot in saxophone, upping his practice schedule from a couple of hours a day to three or four. There’s a video taken around that time, at his high school’s Battle of the Bands. I wish you could see it. Brandon is seventeen, singing lead and straddling the sax in a band called “Ummmxa0.xa0.xa0.xa0,” and he’s deep in his Jim Morrison phase, with dark sunglasses, long curly brown hair, and his shirt unbuttoned to the navel, for which he would later get detention. The following year, he moved to Ohio as a freshman at Oberlin College Conservatory of Music. He declared a major in saxophone performance, but the urge to make something—not just memorize and perform a piece of music that someone else had made—was still there, and in his second year, he added a minor in music composition. After graduation, he moved to New York to work on a master’s at Brooklyn College Conservatory, sharing an apartment in Manhattan with a violinist and an opera singer. Meanwhile, I had left Oklahoma City and headed west to Stanford, where I studied human biology and French and was frequently asleep in my dorm room bunk bed by ten o’clock, though I did flirt with rebellion by cutting my hair short, dyeing it calico, and stealing pre-portioned balls of Otis Spunkmeyer cookie dough from the freezer of my dining hall. When I graduated, I spent a year teaching English in France before moving to Seattle in 2002 to start graduate school in anthropology at the University of Washington. Brandon and I met in 2005, when a friend of his suggested that he read Orangette, the food blog that I had started the previous summer. He did, and then he sent an e-mail to pass on a few choice compliments that evidently were very effective. He described himself as “a musician (composer) getting my master’s part-time in NYC, while being a full-time food snob / philosopher / chef.” Let’s ignore the snob / philosopher part; he was only twenty-three, so he gets a pass. But the chef part! He was referring, I would learn, to his part-time job as a cooking-and-grocery-shopping go-fer for a wealthy uncle, and to the fact that he liked to have friends over to dinner. But, people: I should have seen it. This man was not going to be a composer. By the second letter, he was describing the smell of flaming Calvados on crêpes, and to explain what type of music he wrote, he offered this: I guess it’s considered classical. I usually write for choirs or orchestras or chamber groups, although sometimes I use electronics or make sound sculptures or installations. For a food analogy: I won’t make salads with raw chicken, lychee, pork rinds, and lemon zest with a motor oil, goat cheese, and olive oil dressing, just because no one has done it before. I try to make “dishes” that taste like nothing else, and taste good. Being a composer is really no different from being a chef or a choreographer. I should have seen it, but I didn’t. And until a few months after we were married, I don’t think he did, either. Read more

Features & Highlights

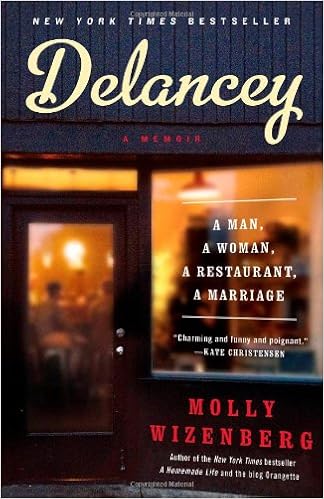

- In this funny, frank, and tender new memoir, the author of the

- New York Times

- bestseller

- A Homemade Life

- and the blog Orangette recounts how opening a pizza restaurant sparked the first crisis of her young marriage.In this funny, frank, tender memoir and

- New York Times

- bestseller, the author of

- A Homemade Life

- and the blog Orangette recounts how opening a restaurant sparked the first crisis of her young marriage. When Molly Wizenberg married Brandon Pettit, he was a trained composer with a handful of offbeat interests: espresso machines, wooden boats, violin-building, and ice cream–making. So when Brandon decided to open a pizza restaurant, Molly was supportive—not because she wanted him to do it, but because the idea was so far-fetched that she didn’t think he would. Before she knew it, he’d signed a lease on a space. The restaurant, Delancey, was going to be a reality, and all of Molly’s assumptions about her marriage were about to change. Together they built Delancey: gutting and renovating the space on a cobbled-together budget, developing a menu, hiring staff, and passing inspections. Delancey became a success, and Molly tried to convince herself that she was happy in their new life until—in the heat and pressure of the restaurant kitchen—she realized that she hadn’t been honest with herself or Brandon. With evocative photos by Molly and twenty new recipes for the kind of simple, delicious food that chefs eat at home,

- Delancey

- is a moving and honest account of two young people learning to give in and let go in order to grow together.