Description

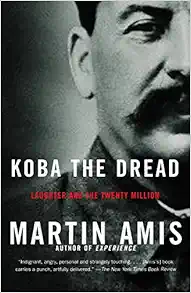

From The New Yorker When the historian Robert Conquest was asked in the post-Gorbachev years to give a new title to a revised edition of "The Great Terror," his classic 1968 account of the murderous Stalin era, he said to his publisher, "How about 'I Told You So, You Fucking Fools'?" Rarely has such smugness been so deeply earned. There had been many fools who dismissed Conquest as a dupe. In this meditation, the novelist Martin Amis sets out to recall the moral and intellectual blindness that allowed so many to ignore the millions of corpses and the camps, and his heroic voices include Conquest (to whom the book is dedicated), Solzhenitsyn, Koestler, and Akhmatova. "Koba the Dread" is a vivid, if often eccentric, rereading of those authors; the frequent instances when the book veers into family memoir and homely analogy, however, are less successful. At one point, Amis writes that the nighttime cries of his baby daughter "would not have been out of place in the deepest cellars of the Butyrki Prison in Moscow during the Great Terror." As it happens, they would have. Copyright © 2005 The New Yorker “ Koba the Dread is filled with passion and intelligence, and with prose that gleams and startles.... This fierce little book...[has the] power to surprise, and ultimately to provoke, enrage and illuminate.” – San Jose Mercury News “Heartfelt.... Amis does not shrink from difficult questions about possible moral distinctions between Lenin and Stalin, Stalin and Hitler.” – San Francisco Chronicle “Riveting...Martin Amis has a noble purpose in writing Koba the Dread . He wants to call attention to just what an insanely cruel monster Josef Stalin was.” – Seattle Times “Martin Amis is our inimitable prose master, a constructor of towering English sentences, and his life…is genuinely worth writing about.” – Esquire From the Inside Flap A brilliant weave of personal involvement, vivid biography and political insight, Koba the Dread is the successor to Martin Amis?s award-winning memoir, Experience . Koba the Dread captures the appeal of one of the most powerful belief systems of the 20th century ? one that spread through the world, both captivating it and staining it red. It addresses itself to the central lacuna of 20th-century thought: the indulgence of Communism by the intellectuals of the West. In between the personal beginnings and the personal ending, Amis gives us perhaps the best one-hundred pages ever written about Stalin: Koba the Dread, Iosif the Terrible.The author?s father, Kingsley Amis, though later reactionary in tendency, was a ?Comintern dogsbody? (as he would come to put it) from 1941 to 1956. His second-closest, and then his closest friend (after the death of the poet Philip Larkin), was Robert Conquest, our leading Sovietologist whose book of 1968, The Great Terror , was second only to Solzhenitsyn?s The Gulag Archipelago in undermining the USSR. The present memoir explores these connections.Stalin said that the death of one person was tragic, the death of a million a mere ?statistic.? Koba the Dread , during whose course the author absorbs a particular, a familial death, is a rebuttal of Stalin?s aphorism. From the Hardcover edition. A brilliant weave of personal involvement, vivid biography and political insight, "Koba the Dread is the successor to Martin Amis's award-winning memoir, "Experience. "Koba the Dread captures the appeal of one of the most powerful belief systems of the 20th century -- one that spread through the world, both captivating it and staining it red. It addresses itself to the central lacuna of 20th-century thought: the indulgence of Communism by the intellectuals of the West. In between the personal beginnings and the personal ending, Amis gives us perhaps the best one-hundred pages ever written about Stalin: Koba the Dread, Iosif the Terrible. The author's father, Kingsley Amis, though later reactionary in tendency, was a "Comintern dogsbody" (as he would come to put it) from 1941 to 1956. His second-closest, and then his closest friend (after the death of the poet Philip Larkin), was Robert Conquest, our leading Sovietologist whose book of 1968, "The Great Terror, was second only to Solzhenitsyn's "The Gulag Archipelago in undermining the USSR. The present memoir explores these connections. Stalin said that the death of one person was tragic, the death of a million a mere "statistic." "Koba the Dread, during whose course the author absorbs a particular, a familial death, is a rebuttal of Stalin's aphorism. "From the Hardcover edition. MARTIN AMIS is the author of 15 novels—among them Zone of Interest, London Fields, Time’s Arrow, The Information, and Night Train —along withxa0the memoir Experience, the novelized self-portrait Inside Story ,xa0two collections of stories, and seven nonfiction books.xa0He died in 2023. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. PART I THE COLLAPSE OF THE VALUE OF HUMAN LIFE PreparatoryHere is the second sentence of Robert Conquest's The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine:We may perhaps put this in perspective in the present case by saying that in the actions here recorded about twenty human lives were lost for, not every word, but every letter, in this book.That sentence represents 3,040 lives. The book is 4411 pages long.'Horse manure was eaten, partly because it often contained whole grains of wheat' (1,340 lives). 'Oleska Voytrykhovsky saved his and his family's ...lives by consuming the meat of horses which had died in the collective of glanders and other diseases' (2,480 lives). Conquest quotes Vasily Grossman's essayistic-documentary novel Forever Flowing: 'And the children's faces were aged, tormented, just as if they were seventy years old. And by spring they no longer had faces. Instead, they had birdlike heads with beaks, or frog heads - thin, wide lips - and some of them resembled fish, mouths open' (3,880 lives). Grossman goes on:In one hut there would be something like a war. Everyone would keep close watch over everyone else ...The wife turned against her husband and the husband against his wife. The mother hated the children. And in some other hut love would be inviolable to the very last. I knew one woman with four children. She would tell them fairy stories and legends so that they would forget their hunger. Her own tongue could hardly move, but she would take them into her arms even though she had hardly the strength to lift her arms when they were empty. Love lived on within her. And people noticed that where there was hate people died off more swiftly. Yet love, for that matter, saved no one. The whole village perished, one and all. No life remained in it.Thus: 11,860 lives. Cannibalism was widely practised - and widely punished. Not all these pitiable anthropophagi received the supreme penalty. In the late 1930s, 325 cannibals from the Ukraine were still serving life sentences in Baltic slave camps.The famine was an enforced famine: the peasants were stripped of their food. On 11 June 1933, the Ukrainian paper Visti praised an 'alert' secret policeman for unmasking and arresting a 'fascist saboteur' who had hidden some bread in a hole under a pile of clover. That word fascist. One hundred and forty lives.In these pages, guileless prepositions like at and to each rep-resent the murder of six or seven large families. There is only one book on this subject: Conquest's. It is, I repeat, 4411 pages long. Credentials I am a fifty-two-year-old novelist and critic who has recently read several yards of books about the Soviet experiment. On 31 December 1999, along with Tony Blair and the Queen, I attended the celebrations at the Millennium Dome in London. Touted as a festival of high technology in an aesthetic dreamscape, the evening resembled a five-hour stopover in a second-rate German airport. For others, the evening resembled a five-hour attempt to reach a second-rate German airport - so I won't complain. I knew that the millennium was a non-event, reflecting little more than our interest in zeros; and I knew that 31 December 1999, wasn't the millennium anyway.* But that night did seem to mark the end of the twentieth century; and the twentieth century is unanimously considered to be our worst century yet (an impression confirmed by the new book I was reading: Reflections on a Ravaged Century, by Robert Conquest). I had hoped that at midnight I would get some sort of chiliastic frisson. And I didn't get it at the Dome. Nonetheless, a day or two later I started to write about the twentieth century and what I took to be its chief lacuna. The piece, or the pamphlet, grew into the slim volume you hold in your hands. I have written about the Holocaust, in a novel (Time's Arrow). Its afterword begins:This book is dedicated to my sister Sally, who, when she was very young, rendered me two profound services. She awakened my protective instincts; and she provided, if not my earliest childhood memory, then certainly my most charged and radiant. She was perhaps half an hour old at the time. I was four.It feels necessary to record that, between Millennium Night and the true millennium a year later, my sister died at the age of forty-six. Background In 1968 I spent the summer helping to rewire a high-bourgeois mansion in a northern suburb of London. It was my only taste of proletarian life. The experience was additionally fleeting and qualified: when the job was done, I promptly moved into the high-bourgeois mansion with my father and stepmother (both of them novelists, though my father was also a poet and critic). My sister would soon move in too. That summer we were of course monitoring the events in Czechoslovakia. In June, Brezhnev deployed 16,000 men on the border. The military option on 'the Czech problem' was called Operation Tumour . . . My father had been to Prague in 1966 and made many contacts there. After that it became a family joke - the stream of Czechs who came to visit us in London. There were bouncing Czechs, certified Czechs, and at least one honoured Czech, the novelist Josef Skvorecky. And then on the morning of 21 August my father appeared in the doorway to the courtyard, where the rewiring detail was taking a break, and called out in a defeated and wretched voice: 'Russian tanks in Prague.'I turned nineteen four days later. In September I went up to Oxford.The first two items in The Letters of Kingsley Amis form the only occasion, in a book of 1,200 pages, where I find my father impossible to recognize. Here he is humourlessly chivvying a faint-hearted comrade to rally to the cause. The tone (earnest, elderly, 'soppy-stern') is altogether alien: 'Now, really, you know, this won't do at all, leaving the Party like that. Tut, tut, John. I am seriously displeased with you.' The second letter ends with a hand-drawn hammer and sickle. My father was a card-carrying member of the CP, taking his orders, such as they were, from Stalin's Moscow. It was November 1941: he was nineteen, and up at Oxford.1941 Kingsley, let us assume, was sturdily ignorant of the USSR's domestic cataclysms. But its foreign policies hardly cried out for one's allegiance. A summary. August 1939: the Nazi-Soviet Pact. September 1939: the Nazi-Soviet invasion-partition of Poland (and a second pact: the Soviet-German Treaty on Borders and Friendship). November 1939: the annexation of Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia, and the attempted invasion of Finland (causing the USSR's expulsion, the following month, from the League of Nations). June 1940: the annexation of Moldavia and Northern Bukovina. August 1940: the annexation of Lithuania, Lativa and Estonia; and the murder of Trotsky. These acquisitions and decapitations would have seemed modest compared to Hitler's helter-skelter successes over the same period. And then in June 1941, of course, Germany attacked the Soviet Union. My father rightly expected to participate in the war; the Russians were now his allies. It was then that he joined the Party, and he remained a believer for fifteen years.How much did the Oxford comrades know, in 1941? There were public protests in the West about the Soviet forced-labour camps as early as 1931. There were also many solid accounts of the violent chaos of Collectivization (1929-34) and of the 1933 famine (though no suggestion, as yet, that the famine was terroristic). And there were the Moscow Show Trials of 1936-38, which were open to foreign journalists and observers, and were monitored worldwide. In these pompous and hysterical charades, renowned Old Bolsheviks 'confessed' to being career-long enemies of the regime (and to other self-evidently ridiculous charges). The pubescent Solzhenitsyn was 'stunned by the fraud-ulence of the trials'. And yet the world, on the whole, took the other view, and further accepted indignant Soviet denials of famine, enserfment of the peasantry, and slave labour. 'There was no reasonable excuse for believing the Stalinist story. The excuses which can be advanced are irrational,' writes Conquest in The Great Terror. The world was offered a choice between two realities; and the young Kingsley, in common with the overwhelming majority of intellectuals everywhere, chose the wrong reality.The Oxford Communists would certainly have known about the Soviet decree of 7 April 1935, which rendered children of twelve and over subject to 'all measures of criminal punishment', including death. This law, which was published on the front page of Pravda and caused universal consternation (reducing the French CP to the argument that children, under socialism, became grownups very quickly), was intended, it seems, to serve two main purposes. One was social: it would expedite the disposal of the multitudes of feral and homeless orphans created by the regime. The second purpose, though, was political. It applied barbaric pressure on the old oppositionists, Kamenev and Zinoviev, who had children of eligible age; these men were soon to fall, and their clans with them. The law of 7 April 1935, was the crystallization of 'mature' Stalinism. Imagine the mass of the glove that Stalin swiped across your face; imagine the mass of it.**On 7 April 1935 my father was nine days away from his thirteenth birthday. Did he ever wonder, as he continued to grow up, why a state should need 'the last line of defence' (as a secret reinforcing instruction put it) against twelve-year-olds?Perhaps there is a reasonable excuse for believing the Stalinist story. The real story - the truth - was entirely unbelievable.* The millennial moment was midnight, 31 December 2000 This is because we went from B.C. to A.D. without a year nought. Vladimir Putin described the (pseudo) millennium as 'the 2000th anniversary of Christianity'.** It will be as well, here, to get a foretaste of his rigour. The fate of Mikhail Tukhachevsky, a famous Red commander in the Civil War, was ordinary enough, and that of his family was too. Tukhachevsky was arrested in 1937, tortured (his interrogation protocols were stained with drops of 'flying' blood, suggesting that his head was in rapid motion at the time), farcically arraigned, and duly executed. Moreover (this is Robert C. Tucker's précis in Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1928-41): 'His wife and daughter returned to Moscow where she was arrested a day or two later along with Tukhachevsky's mother, sisters, and brothers Nikolai and Aleksandr. Later his wife and both brothers were killed on Stalin's orders, three sisters were sent to camps, his young daughter Svetlana was placed in a home for children of "enemies of the people" and arrested and sent to a camp on reaching the age of seventeen, and his mother and one sister died in exile.' Read more

Features & Highlights

- A brilliant weave of personal involvement, vivid biography and political insight,

- Koba the Dread

- is the successor to Martin Amis’s award-winning memoir,

- Experience

- .

- Koba the Dread

- captures the appeal of one of the most powerful belief systems of the 20th century — one that spread through the world, both captivating it and staining it red. It addresses itself to the central lacuna of 20th-century thought: the indulgence of Communism by the intellectuals of the West. In between the personal beginnings and the personal ending, Amis gives us perhaps the best one-hundred pages ever written about Stalin: Koba the Dread, Iosif the Terrible. The author’s father, Kingsley Amis, though later reactionary in tendency, was a “Comintern dogsbody” (as he would come to put it) from 1941 to 1956. His second-closest, and then his closest friend (after the death of the poet Philip Larkin), was Robert Conquest, our leading Sovietologist whose book of 1968,

- The Great Terror

- , was second only to Solzhenitsyn’s

- The Gulag Archipelago

- in undermining the USSR. The present memoir explores these connections. Stalin said that the death of one person was tragic, the death of a million a mere “statistic.”

- Koba the Dread

- , during whose course the author absorbs a particular, a familial death, is a rebuttal of Stalin’s aphorism.