Description

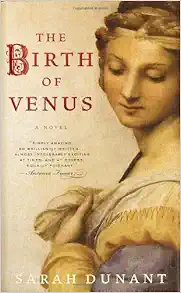

From Publishers Weekly Starred Review. Dunant ( The Birth of Venus ) revisits 16th-century Italy, where the convents are filled with the daughters of noblemen who are unable or unwilling to pay a dowry to marry them off. The Santa Caterina convent's newest novice, Serafina, is miserable, having been shunted off by her father to separate her from a forbidden romance. She also has a singing voice that will be the glory of the convent and—more importantly to some—a substantial bonus for the convent's coffers. The convent's apothecary, Suora Zuana, strikes up a friendship with Serafina, enlisting her as an assistant in the convent dispensary and herb garden, but despite Zuana's attempts to help the girl adjust, Serafina remains focused on escaping. Serafina's constant struggle and her faith (of a type different from that common to convents) challenge Zuana's worldview and the political structure of Santa Caterina. A cast of complex characters breathe new life into the classic star-crossed lovers trope while affording readers a look at a facet of Renaissance life beyond the far more common viscounts and courtesans. Dunant's an accomplished storyteller, and this is a rich and rewarding novel. (Aug.) Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. From Bookmarks Magazine British author Dunant expertly weaves the rhythms of daily convent life within the broader context of church politics and reform. Most critics were pleasantly surprised that a novel set in a nunnery could be fraught with such tension as they wondered, a bit nervously, about Serafina's ultimate fate. Dunant continues to create believable characters who were also very much women of their time. Several reviewers noted a sluggish beginning and occasional dry passages, but they believed readers would be rewarded for their patience. Ultimately, critics hailed Dunant as a skilled historian and accomplished storyteller who has written another engrossing, rewarding tale of the Italian Renaissance. “A cast of complex characters breathe new life into the classic star-crossed lovers trope while affording readers a look at a facet of Renaissance life beyond the far more common viscounts and courtesans. Dunant’s an accomplished storyteller, and this is a rich and rewarding novel.”– Publishers Weekly , starred review“Dunant's brilliant imagination is at its powerful best as she re-creates the routines, the crotchets and tiny details of convent life in 1570. The reader can hear the rustle of nuns' habits and the murmur of their prayers….[a] captivating novel…packed with complex relationships, passion, sorrow and religious devotion….this novel unequivocally does what fiction is supposed to do and rarely does: It takes us to a place we could never personally experience. Dunant creates such a living and tangible environment, built on meticulous yet unobtrusive research, that she shares with us the joys and sorrows, the frustration and anger, the rebellion, submission and sometimes even the presence of God.”— Washington Post “A great read that throws a light in a hidden corner of history, with a bonus: Although written for a secular crowd, it never discounts the possibility of miracles.”— Cleveland Plain Dealer “Engrossing…. Dunant brings the period vividly to life, portraying in detail the complex, claustrophobic world of the convent.” — Boston Globe “Original, engrossing, meticulously researched, this is a fascinating tale….This novel has everything: period detail, political intrigue, love, mystery, social strife, and epic cattiness.” — Elle Sarah Dunant is the author of the international bestsellers The Birth of Venus and In the Company of the Courtesan , which have received major acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic. Her earlier novels include three Hannah Wolfe crime thrillers, as well as Snowstorms in a Hot Climate , Transgressions , and Mapping the Edge, all three of which are available as Random House Trade Paperbacks. She has two daughters and lives in London and Florence. From The Washington Post From The Washington Post's Book World/washingtonpost.com Reviewed by Brigitte Weeks Sarah Dunant's previous best-selling novel, "In the Company of the Courtesan," was entirely devoted to the platonic relationship between an elegant and tough-minded prostitute and her manager, a highly sophisticated dwarf. Given the unlikely subject matter, the novel's international success cast welcome doubt on the publishing world's conviction that only froth sells fiction and that romance can only succeed by starring two gorgeous protagonists. Now, in "Sacred Hearts," the British novelist has found another unusual cast of characters: residents of the convent of Santa Caterina in the Italian city of Ferrara. Dunant's brilliant imagination is at its powerful best as she re-creates the routines, the crotchets and tiny details of convent life in 1570. The reader can hear the rustle of nuns' habits and the murmur of their prayers. The women, having given up all external freedoms, live under the rule of the Benedictine order. That means total obedience, even including what they may do with their eyes -- always keep them focused on the ground -- and how they may ask to break the Great Silence. This kingdom is ruled over by Abbess Madonna Chiara, who has lived within the high walls, behind the locked gate, since the she was a child. But despite this restricted life she has kept a close eye on the economics and politics of the world outside. She is an intriguing mixture of icy ruler and accomplished negotiator. This captivating novel opens with the arrival of a new candidate for the order, a novice, who from the moment she turns up disturbs the silence of the convent. Her new name as an apprentice nun is to be Serafina. She has been forced into the convent by her family when she rejected the suitor selected by her father and clung to Jacopo, her romantic but lowborn music teacher. The wealthy suitor was accepted for her younger, more biddable sister, and the convent gates closed behind Serafina forever. This fate, having nothing at all to do with the girls' religious calling, was not unusual in large, aristocratic families of the day. Often they could not afford to provide the dowry for more than one daughter. Girls of that class couldn't work, were costly to maintain at home and ultimately became an embarrassment to the family. So as the price of marriage grew more and more expensive, the convents gladly received unwed girls whose families paid substantial fees. The convents prospered and took on lifelong responsibility for surplus females, while as a side benefit, the family's reputation for piety was enhanced. Dunant points out in her introduction that in the city-states of 16th-century Italy up to half of all noblewomen became nuns, and "not all of them went willingly." So, Serafina's younger sister gets the wedding ring, and Serafina becomes a bride of Christ. This young woman, however, is convinced that her music teacher lover "will not let her rot in here. . . . No, he will not forget her. In some way or other he will find her, just as he said he would. Until then she will make herself ready and bide her time, and whatever happens she will not let the fire inside get the better of her." Although reputed to have an exceptional singing voice, Serafina refuses to sing a single note. "Songbirds don't sing when they are kept in the dark," she tells Suora Zuana, the dispensary mistress, charged with her care. Angry at her family and bitter at her incarceration, she screams "as if a wayward troop of devils" had invaded her cell. Even before Serafina's noisy arrival, though, tension has swirled beneath the ordered surface of the convent. "Sacred Hearts" is packed with complex relationships, passion, sorrow and religious devotion. Some sisters live entirely in the service of God, endlessly depriving themselves of food and any comfort. Others use the protection of the convent to nurture their musical and artistic talents. But masked by their obedience to the daily routine, there is increasing conflict between nuns entirely focused on seeking the grace of God and those who prefer to please themselves. Suora Perseveranza, one of the former, is "in thrall to the music of suffering." She wears "a leather belt nipped around her waist, a series of short nails on the inside, a few so deeply embedded in the flesh beneath that all that can be seen are the crusted swollen wounds." Another nun, Suora Ysbeta, bestows her affections on a pet dog she keeps "swaddled like a baby in satin cloth." Suora Umiliana, the nun in charge of the novices, sees such worldly activities as the work of the devil. The conflict deepens as every sister is pressed by her companions to join either with those for absolute obedience or those clinging to their small diversions. As Serafina's despair deepens, Suora Zuana guides her through the increasing stresses in the convent. She has made her peace with the cloistered life, even though she does not feel the closeness to God that sustains some of her companions. Serafina is assigned to assist her in the dispensary, and Zuana's gentle compassion builds a relationship between them. The dispensary mistress, who learned healing skills from her late father, knows that in the outside world a woman could never practice any kind of medicine. But in the convent, her healing skills are welcomed and respected. Although a plot with an entirely female cast within a confined world may not sound engrossing, this novel unequivocally does what fiction is supposed to do and rarely does: It takes us to a place we could never personally experience. Dunant creates such a living and tangible environment, built on meticulous yet unobtrusive research, that she shares with us the joys and sorrows, the frustration and anger, the rebellion, submission and sometimes even the presence of God in the lives of a handful of nuns in 16th-century Italy. Copyright 2009, The Washington Post. All Rights Reserved. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. Chapter One Before the screaming starts, the night silence of the convent is already alive with its own particular sounds.In a downstairs cell, Suora Ysbeta’s lapdog, swaddled like a baby in satin cloth, is hunting in its dreams, muzzled grunts and growls marking the pleasure of each rabbit cornered. Ysbeta herself is also busy with the chase, her silver tray doubling as a mirror, her right hand poised as she closes a pair of tweezers over a stubborn white hair on her chin. She pulls sharply, the sting and the satisfaction of the release in the same short aah of breath.Across the courtyard two young women, plump and soft-cheeked as children, lie together on a single pallet, entwined like kindling twigs, their faces so close they seem almost to be exchanging breaths, the one inhaling as the other lets go: in, out, in, out. There is a slight sweetness to the air—angelica, perhaps, or sweet mint—as if they have both eaten the same sugared cake or drunk from the same spiced wine cup. Whatever they have imbibed, it has left them both sleeping soundly, their contentment a low hum of pleasure in the room.Suora Benedicta, meanwhile, can barely contain herself, there is so much music inside her head. Tonight it is a setting of the Gradual for the Feast of the Epiphany, the different voices like colored tapestry threads weaving in and over one another. Sometimes they move so fast she can barely chalk them down, this stream of white notes on her slate blackboard. There are nights when she doesn’t seem to sleep at all, or when the voices are so insistent she is sure she must be singing out loud with them. Still, no one admonishes her the next day, or wakes her if she slips into a sudden nap in the refectory. Her compositions bring honor and benefactors to the convent, and so her eccentricities are overlooked.In contrast, young Suora Perseveranza is in thrall to the music of suffering. A single tallow candle spits shadows across her cell. Her shift is so thin she can feel the winter damp as she leans back against the stone wall. She pulls the cloth up over her calves and thighs, then more carefully across her stomach, letting out a series of fluttering moans as the material sticks and catches on the open wounds underneath. She stops, breathing fast once or twice to still herself, then tugs harder where she meets resistance, until the half-formed skin tears and lifts off with the cloth. The candlelight reveals a leather belt nipped around her waist, a series of short nails on the inside, a few so deeply embedded in the flesh beneath that all that can be seen are the crusted swollen wounds where leather and skin have fused together. Slowly, deliberately, she presses on one of the studs. Her hand jumps back involuntarily, a cry bursting out of her, but there is an exhilaration to the sound, a challenge to herself as her fingers go back again.She keeps her gaze fixed on the wall ahead, where the guttering light picks out a carved wooden crucifix: Christ, young, alive, His muscles running through the grain as His body strains forward against the nails, His face etched with sorrow. She stares at Him, her own body trembling, tears wet on her cheeks, her eyes bright. Wood, iron, leather, flesh. Her world is contained in this moment. She is within His suffering; He is within hers. She is not alone. Pain has become pleasure. She presses the stud again and her breath comes out in a long satisfying growl, almost an animal sound, consumed and consuming.In the next-door cell, Suora Umiliana’s fingers pause briefly over her chattering rosary beads. The sound of the young sister’s devotion is like the taste of honey in her mouth. When she was younger she too had sought God through open wounds, but now as novice mistress it is her duty to put the spiritual well-being of others before her own. She bows her head and returns to her beads....in her cell above the infirmary, Suora Zuana, Santa Caterina’s dispensary mistress, is busy with her own kind of prayer. She sits bent over Brunfels’s great book of herbs, her forehead creased in concentration. Next to her is a recently finished sketch of a geranium plant, the leaves of which have proved effective at stanching cuts and flesh wounds—one of the younger nuns has started passing clots of blood, and she is searching for a compound to stop a wound she cannot see.Perseveranza’s moans echo along the upper cloister corridor. Last summer, when the heat brought the beginnings of infection to the wounds and those who sat next to the young nun in chapel complained about the smell, the abbess had sent her to the dispensary for treatment. Zuana had washed and dressed the angry lesions as best she could and given her ointment to reduce the swelling. There is nothing more she can do. While it is possible that Perseveranza might eventually poison herself with some deeper infection, she is healthy enough otherwise, and from what Zuana knows of the way the body works she doesn’t think this will happen. The world is full of stories of men and women who live with such mutilations for years, and while Perseveranza might talk fondly enough of death, it is clear that she gains too much joy from her suffering to want to end it prematurely.Zuana herself doesn’t share this passion for self-mortification. Before she came to the convent she had lived for many years as the only child of a professor of medicine. His very reason for being alive had been to explore the power of nature to heal the body, and she cannot remember a moment in her life when she didn’t share his fervor. She would have made a fine doctor or teacher like him, had such a thing been possible. As it is, she was fortunate that after his death his name and his estate were good enough to buy her a cell in the convent of Santa Caterina, where so many noblewomen of Ferrara find space to pursue their own ways to live inside God’s protection.Still, any convent, however well adjusted, trembles a little when it takes in one who really does not want to be there....zuana looks up from her table. The sobbing coming from the recently arrived novice’s cell is now too loud to be ignored. What started as ordinary tears has grown into angry howls. As dispensary mistress it is Zuana’s job, should things become difficult, to settle any newcomer by means of a sleeping potion. She turns over the hourglass. The draft is already mixed and ready in the dispensary. The only question is how long she should wait.It is a delicate business, judging the depth of a novice’s distress. A certain level of upset is only natural: once the feasting is over and the family has left, the great doors bolted behind them, even the most devout of young women can suffer a rush of panic when faced with the solitude and silence of the closed cell.Those with relatives inside are the easiest to settle. Most of them have cut their teeth on convent cakes and biscuits, so pampered and fussed over through years of visiting that the cloister is already a second home. If—as it might—the day itself unleashes a flurry of exhausted tears, there is always an aunt, sister, or cousin on hand to cajole or comfort them.For others, who might have harbored dreams of a more flesh-and-blood bridegroom or left a favorite brother or doting mother, the tears are as much a mourning for the past as fear of the future. The sisters in charge treat them gently as they clamber out of dresses and petticoats, shivering from nerves rather than cold, their naked arms raised high in the air in readiness for the shift. But all the care in the world cannot disguise the loss of freedom, and though some might later substitute silk for serge (such fashionable transgressions are ignored rather than allowed), that first night girls with soft skin and no proclivity for penance can be driven mad by the itch and the scratch. These tears have an edge of self-pity to them, and it is better to cry them now, for they can become a slow poison if left to fester.Eventually the storm will blow itself out and the convent return to sleep. The watch sister will patrol the corridors, keeping tally of the time until Matins, some two hours after midnight, at which point she will pass through the great cloister in the dark, knocking on each door in turn but missing that of the latest arrival. It is a custom in Santa Caterina to allow the newcomer to spend her first night undisturbed, so the next day will find her refreshed and better prepared to enter her new life.Tonight, however, no one will do much sleeping.In the bottom of the hourglass the hill of sand is almost complete, and the wailing has grown so violent that Zuana feels it in her stomach as well as her head—as if a wayward troop of devils has forced its way inside the girl’s cell and is even now winding her intestines on a spit. In their dormitory, the young boarders will be waking in terror. The hours between Compline and Matins mark the longest sleep of the night, and any disturbance now will make the convent bleary-eyed and foul-tempered tomorrow. In between the screams, Zuana registers a cracked voice rising up in tuneless song from the infirmary. Night fevers conjure up all manner of visions among the ill, not all of them holy, and it will not help to have the crazed and the sickly joining in the chorus.Zuana leaves her cell swiftly, her feet knowing the way better than her eyes. As she moves down the stairs into the main cloister and enters the great courtyard, she is held for a second, as she often is, by its sheer beauty. From the moment she first stood here, sixteen years ago, the walls around threatening to crush her, it has offered a space for peace and dreams. By day the air is so still it seems as if time itself has stopped, while in the dark you can almost hear the rush of angels’ wings behind you. Not tonight, though. Tonight the stone well in the middle looms up like a gray ship in a sea of black, the sound of... Read more

Features & Highlights

- The year is 1570, and in the convent of Santa Caterina, in the Italian city of Ferrara, noblewomen find space to pursue their lives under God’s protection. But any community, however smoothly run, suffers tremors when it takes in someone by force. And the arrival of Santa Caterina’s new novice sets

- in motion a chain of events that will shake the convent to its core.Ripped by her family from an illicit love affair, sixteen-year-old Serafina is willful, emotional, sharp, and defiant–young enough to have a life to look forward to and old enough to know when that life is being cut short. Her first night inside the walls is spent in an incandescent rage so violent that the dispensary mistress, Suora Zuana, is dispatched to the girl’s cell to sedate her. Thus begins a complex relationship of trust and betrayal between the young rebel and the clever, scholarly nun, for whom the girl becomes the daughter she will never have.As Serafina rails against her incarceration, others are drawn into the drama: the ancient, mysterious Suora Magdalena–with her history of visions and ecstasies–locked in her cell; the ferociously devout novice mistress Suora Umiliana, who comes to see in the postulant a way to extend her influence; and, watching it all, the abbess, Madonna Chiara, a woman as fluent in politics as she is in prayer. As disorder and rebellion mount, it is the abbess’s job to keep the convent stable while, outside its walls, the dictates of the Counter-Reformation begin to purge the Catholic Church and impose on the nunneries a regime of terrible oppression.Sarah Dunant, the bestselling author of

- The Birth of Venus

- and In the

- Company of the Courtesan

- , brings this intricate Renaissance world compellingly to life. Amid

- Sacred Hearts

- is a rich, engrossing, multifaceted love story, encompassing the passions of the flesh, the exultation of the spirit, and the deep, enduring power of friendship.